GUEST CURATOR: Olivia Burke

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

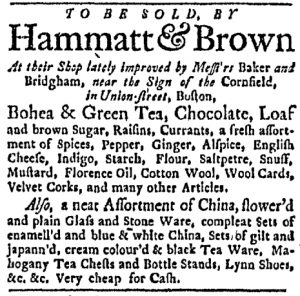

“A neat Assortment of China, flower’d and plain Glass and Stone Ware.”

Advertisements like this were very common in newspapers in the latter half of the eighteenth century. Hammatt and Brown had for sale an impressive list of goods, including tea, chocolate, cotton wool and a “neat Assortment” of china, glass, and stoneware. This advertisement displayed the expanding consumer culture in the colonies. No longer were people producing things for self-sufficiency. As T.H. Breen explains, “[A] pioneer world of homespun cloth and wooden dishes … was swept away by a flood of store-bought sundries.”[1] Colonists became interested in things and what those material goods did for their image. This change also led to an emergence of a commonalities and a community mindset among colonists of different areas. For example, in “Baubles of Britain”; The American and Consumer Revolutions of the Eighteenth Century,” Breen describes a “shared language of consumption.”[2] People in the colonies had this newfound connection with each other. A colonist from Massachusetts would see the type of fabric a visitor from a southern colony wore and immediately know the material and social class that went with it. This created a common connection among people and subsequently grew a feeling of nationalism through the colonies as the imperial crisis with Britain drew to its boiling point.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

As Olivia indicates, advertisements of this sort were indeed commonly inserted in eighteenth-century newspapers, especially in those published in the largest port cities. Although they ran in every newspaper printed in the colonies, they appeared in greater numbers and with greater frequency in publications from Boston, Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia. In each of those cities, advertisers contended not only with competitors who placed advertisements in the same newspapers they did but also with rival merchants and shopkeepers who advertised in other newspapers as well as those who did not advertise at all. The advertisements in the Boston Evening-Post, for instance, reveal only a small portion of the commercial landscape that made consumer goods available in colonial Massachusetts.

When they decided to advertise the assortment of goods they sold at their shop in Union Street, Hammatt and Brown chose from among several newspapers published in Boston. The Boston Chronicle, the Boston Evening-Post, the Boston-Gazette, the Boston Post-Boy, and Green and Russell’s Massachusetts Gazette were all published on Mondays. A second issue of the Boston Chronicle came out on Thursdays, along with the Boston Weekly News-Letter and Draper’s Massachusetts Gazette. Each included an array of advertisements that hawked the same kinds of wares that Hammatt and Brown listed in their notice. Some merchants and shopkeepers opted to advertise in more than one publication, but others, like Hammatt and Brown, confined themselves to a single newspaper. Among them, advertisers created sufficient copy to barrage colonial readers and potential customers with lists of goods and encouragement to acquire them. Advertising often accounted for as much as half or more of each newspaper. Advertisers submitted so many notices to T. and J. Fleet’s printing office that the issue of the Boston Evening-Post that carried Hammatt and Brown’s advertisement was accompanied by a two-page supplement comprised entirely of advertisement, including Thomas Knight’s advertisement that listed almost all of the same merchandise. Elsewhere in the colonies, other newspapers carried advertisements that peddled similar inventory, contributing to a shared experience, as both readers and consumers, among colonists from New Hampshire to Georgia.

**********

[1] Breen, “‘Baubles of Britain’: The American and Consumer Revolutions of the Eighteenth Century,” Past and Present 119, (May 1988): 78

[2] Breen, 76.