GUEST CURATOR: Daniel McDermott

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

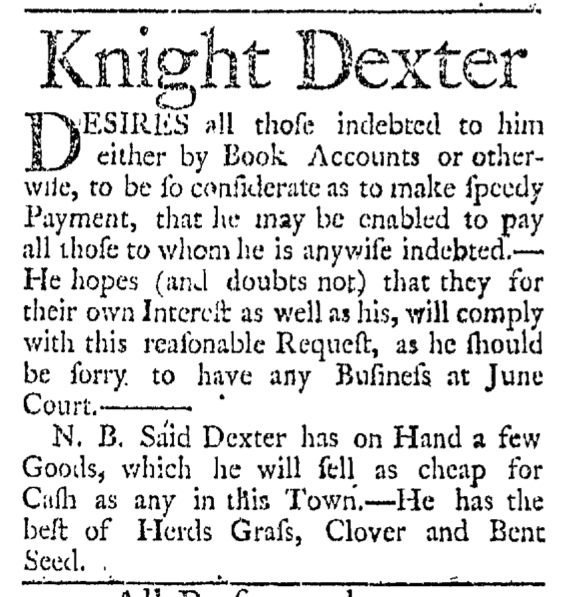

“Knight Dexter DESIRES all those indebted to him … to make speedy Payment.”

Knight Dexter put out this advertisement for those indebted to him to pay their bills. His customers bought on credit rather than paying at the time of purchase. Credit was one of the more popular means for buying items. The other, less popular, means were barter (trading goods for other goods) and paying with physical money.

The concept of credit in colonial America and its importance are both similar to today’s standards. Merchants allowed customers to purchase items in exchange for payment that would occur later in time, with interest included. According to David T. Flynn, this was an advantage to customers who could purchase items outside their financial resources. T.H. Breen argues that this helped create a consumer revolution in the eighteenth century. In “Baubles of Britain,” he details the variety and number of options for consumers that increased, paid for by credit.[1] The advantage for merchants was they could turn over goods faster and they would increase their profits from the interest collected. Merchants did run the risk of giving out too much credit that they could not cover their immediate expenses.

Dexter mentioned “Book Accounts.” This most likely meant he was using book credit, according to Flynn. Book credit was when merchants recorded who they gave credit to within their account books or ledger. This was a way to streamline tracking who owed how much money for what products. Other forms of credit included overseas credit and promissory notes. Dexter might have benefited from overseas credit extended by English merchants when he received imported goods. English merchants sold goods to colonial merchants, waiting six months to one year before demanding payment.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Last week I noted that as spring approached in 1767 the Providence Gazette experienced a resurgence in advertising after several months of only a small number of paid notices within its pages combined with running the same few advertisements repeatedly. Knight Dexter was among the local entrepreneurs who began inserting notices in the Providence Gazette, along with Nathaniel Jacobs. Not only did their advertisements appear one after the other in the same column of the March 14 issue, Dexter and Jacobs adopted parallel structures for their notices.

Marketing goods for sale may not have been the primary purpose either had in mind when they decided to place their advertisements. Both Dexter and Jacobs devoted half or more of their notices to calling on former customs with outstanding debts to visit their shops and settle up accounts. Both threatened legal action against any recalcitrant customers who refused to do so, though Jacobs was much more subtle and polite when he claimed that he wanted to “avoid the disagreeable Necessity of troubling them.” Dexter was more blunt, lamenting that “he should be sorry to have any Business at June Court.” Either way, the message was the same: pay up or face the consequences.

Only after dispensing with that bit of business did either shopkeeper turn to marketing their current inventory. Each promised to “sell as cheap for Cash as any in this Town.” At the same time they called on customers to pay their bills, neither seemed inclined to extend more credit to anyone else, but they balanced their insistence on paying cash with the allure of low prices.

In so doing, they placed what might be considered hybrid advertisements that amalgamated what otherwise might have been separate notices. In each case, the portion of the advertisement that promoted items they currently stocked could have run separately and not looked out of place. Indeed, other advertisements on the same page mirrored the second half of the notices inserted by Dexter and Jacobs. The Adverts 250 Project regularly features similar advertisements. Many merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans frequently placed notices requesting that customers pay their bills, though those have not been examined nearly as often on the Adverts 250 Project. In choosing Knight Dexter’s advertisement, Daniel helps to demonstrate the various stages of commercial relationships established between consumers and retailers in the eighteenth century.

**********

[1] T.H. Breen, “‘Baubles of Britain’: The American and Consumer Revolutions of the Eighteenth Century,” Past and Present 119 (May 1988): 73-104.