GUEST CURATOR: Maria Lepak

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

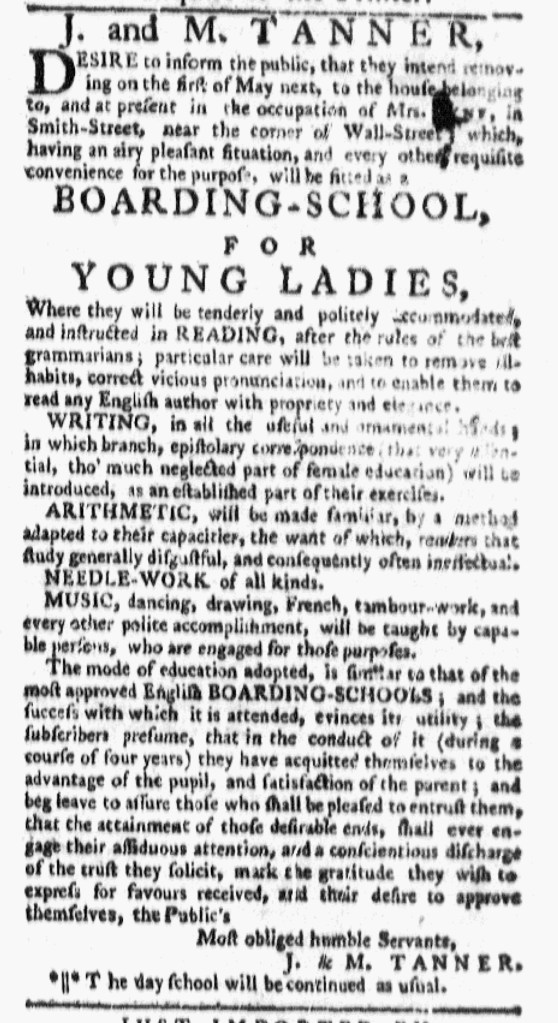

“BOARDING-SCHOOL, FOR YOUNG LADIES.”

J. & M. Tanner’s notice in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer advertised an opportunity for young women to attend a boarding school “in Smith-Street, near the corner of Wall Street.” At this school, the “YOUNG LADIES” would improve in reading, writing, needlework, music, dancing, and other subjects considered appropriate for them. The Tanners include a comparison of their new school to what a British boarding school had to offer, stating that their curriculum “was similar to that of the most approved English BOARDING-SCHOOLS.” According to Mary Cathcart Borer in Willingly to School: A History of Women’s Education, boarding schools for young ladies popped up in England as early as 1711, with nearly the same curriculum at each.[1] However, arithmetic was a subject that the Tanners’ school in the colonies included that many British schools for girls and young women did not. While still expected to stay in the private sphere, Tanners’ boarding school allowed for young women’s opportunities in arithmetic, which was not always an option for many young women elsewhere. We cannot conclude exactly why the Tanners chose to incorporate arithmetic into their school’s curriculum. However, it indicates that while still using the British model, there were variations of the boarding school systems in the colonies.

The Tanners’ boarding school seems to have been an effort to demonstrate that the colonies could also partake in the same developments that England did, particularly in women’s education and manners. Considering that this advertisement was published in 1774, a year before the first battles of the American Revolution, tensions increasingly inspired colonists to establish self-sufficiency in government and commerce and other aspects of life, such as education, without reliance on Britain. Even as that happened, it is critical to recognize that while the colonies were looking to have their own self-sufficient systems and government, they still included British ideals. Britain was still influential in colonial culture, which was especially shared through ideas of education and what made well-educated and well-mannered young ladies.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Rather than expand on Maria’s interpretation of today’s advertisement, I am reflecting on pedagogy and my experiences integrating the Adverts 250 Project and the Slavery Adverts 250 Project into the courses I teach at Assumption University. Throughout this academic year, including the time that Maria and her peers were enrolled in my Revolutionary America course last fall, faculty and staff have engaged in a series of programs about “awaken[ing] in students a sense of wonder” and how we seek to fulfill the University’s mission. I have learned some valuable lessons along the way, from my colleagues at those events and from my students in the classroom.

Maria and her classmates commence their responsibilities as guest curators by compiling a mini-archive of newspapers published during a particular week in 1774. I provide each of them with a list of extant newspapers that have been digitized and train them in using several databases. Once they have created their mini-archives, each student examines the newspapers for their week to identify all of the advertisements about enslaved people for inclusion in the Slavery Adverts 250 Project and to select an advertisement about consumer goods or services to feature on the Adverts 250 Project. I provide students with hard copies of their newspapers, encouraging them to work back and forth with the digitized ones.

One morning last fall, I arrived in class intending to discuss advertisements about enslaved people and what students learned from that portion of the project. We had a robust discussion, but, to my initial frustration, students did not stick to the topic for the day! Instead of focusing solely on advertisements about enslaved people, they started discussing other kinds of advertisements and asking about other aspects of the newspapers as well. I had a lesson plan, an “agenda” of material that I “needed” to cover that day, and their “off-topic” questions did not facilitate the good order that I had envisioned.

Then I realized that I was witnessing authentic wonder in my classroom, that the conversation taking place was more important than anything I scripted in my mind in advance, and that students were learning more from the experience than by following my outline for that class. I spend so much time working with (digitized) eighteenth-century newspapers that they are as familiar to me as modern media … but having a week’s worth of newspapers published in 1774 in front of them was completely new to my students. The advertisements were new to them, but so were the conventions of eighteenth-century print culture! They immersed themselves in their newspapers, learning as much as they could on their own and then asking questions about life in early America based on what they encountered in those newspapers.

When I finally understood what was happening, I jettisoned my outline so we could have a lengthy conversation about anything my students found interesting or confusing or strange in their newspapers. However unintentional, my first instinct had been to stifle their sense of wonder by attempting to rigidly follow my outline for that class. In the end, we all – professor and students – got so much more out of that class when I learned from my students that I could better facilitate how they learned about the past by giving them opportunities to express their wonder. As the semester progressed, we circled back, repeatedly, to discussing advertisements about enslaved people as my students worked on the Slavery Adverts 250 Project. At the same time, I allowed for more opportunities to “get off track” as we examined a variety of other primary sources. My students learned more and I had a more fulfilling experience as an instructor, energized by the quality of the discussions we had in class on those occasions that my students deviated from what I planned for the day.

**********

[1] Mary Cathcart Borer, Willingly to School: A History of Women’s Education (Cambridge, UK: Lutterworth Press, 1976).