What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

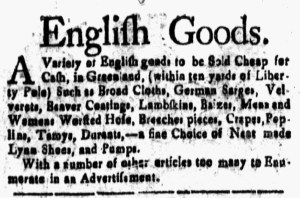

“English Goods … within ten yards of Liberty Pole.”

An anonymous advertiser hawked “A Variety of English goods” in the November 21, 1775, edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette. The notice included a short list of imported items, mostly textiles, such as “Broad Cloths, … Velverets, … Poplins, Tamys, [and] Durants,” as well as “Mens and Womens Worsted Hose [and] Breeches pieces.” That list apparently did not cover everything available for sale; the advertisement concluded with a note about “a number of other articles too many to Enumerate in an Advertisement.”

That may have been the advertiser’s choice since some merchants and shopkeepers did occasionally resort to similar language, though it may have been a decision influenced by the printer, Daniel Fowle. That issue of the New-Hampshire Gazette consisted of only two pages instead of the usual four. It was the first issue of the New-Hampshire Gazette since November 8. The printer did not produce and circulate an issue the previous week. The Adverts 250 Project has tracked apparent disruptions in the supply of paper that had an impact on the New-Hampshire Gazette, yet that was not the only difficulty the printer faced. In the monumental History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820, Clarence S. Brigham notes that Fowle announced that he printed the November 2 edition “‘with great difficulty’ because of the threatened British attack on Portsmouth” and that the printer “stated that the press ‘is removed to Greenland, about six miles from Portsmouth.”[1] Those circumstances may have played a role in the decision to publish an abbreviated advertisement that promised a greater selection of goods than appeared in print.

The advertisement presents other questions about consumer culture during the era of the American Revolution. The Continental Association, a nonimportation and nonconsumption agreement devised by the First Continental Congress, was in effect, yet the unnamed advertiser boldly marketed imported goods. The headline, “English Goods,” appeared in a larger font than anything else in that issue except for the title of the newspaper in the masthead. The advertiser conveniently did not mention when the goods had arrived in the colonies, whether they had been transported and delivered before the boycott went into effect. Yet the advertiser did acknowledge current events when giving the location to purchase the imported goods: “within ten yards of [the] Liberty Pole” in Greenland. In his recent book on the consumption and politics of tea during the era of the American Revolution, James R. Fichter argues that many tea retailers did not face repercussions while tea importers certainly did. He further contends that advertisements revealed the reality of local commerce compared to the propaganda that appeared in news articles and editorials about tea.[2] Perhaps something similar occurred with these “English Goods” in Greenland in the late fall of 1775.

**********

[1] Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820 (American Antiquarian Society, 1947), 471.

[2] James Fichter, “Truth in Advertising,” in Tea: Consumption, Politics, and Revolution, 1773-1776 (Cornell University Press, 2023), 132-157.