What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

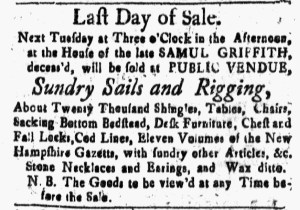

“Last Day of Sale.”

The executors for Samuel Griffith’s estate held a sale in Portsmouth on June 14, 1774, advertising a “PUBLIC VENDUE” in the June 10, 1774, edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette. The sale included “Sundry Sails and Rigging” as well as “About Twenty Thousand Shingles, Tables, Chairs, [a] Sacking Bottom Bedstead, Desk Furniture, …with sundry other Articles” that prospective buyers could view prior to the sale.

Griffith had apparently kept abreast of the news. His estate included “Eleven Volumes of the New Hampshire Gazette,” a “HISTORICAL CHRONICLE” (according to the masthead) of events in the colony and throughout the Atlantic world. The executors considered Griffith’s collection of newspapers of significant enough interest to merit mention in the sale notice. Griffith had not treated his copies of the New-Hampshire Gazette as ephemeral. If those “Eleven Volumes” corresponded with the past eleven years, then buyers could acquire an account of the imperial crisis as it had unfolded with the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the passage and repeal of the Stamp Act in 1765 and 1766, the Townshend Acts and nonimportation agreements in the late 1760s, the Boston Massacre in 1770, and the Boston Tea Party in 1773. Some colonizers, like Harbottle Dorr, revisited news and editorials to inform their understanding of current events.

To incite interest and increase the number of people in attendance, the executors included a headline that proclaimed, “Last Day of Sale.” That alerted readers that they had limited opportunity to acquire any of the items from the estate, likely at bargain prices for secondhand wares compared to what they would pay retail for new items. Those interested in the sails, rigging, and shingles for their own businesses also had the potential for lower prices than purchasing them elsewhere on the market, but not if they hesitated. They needed to be present the following Tuesday when the sale commenced. Many advertisements in the New-Hampshire Gazette did not feature headlines at all, so one announcing “Last Day of Sale” likely helped draw attention to an event soon to take place.