What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“(The Particulars will be in our next.)”

Several shopkeepers advised readers of the Connecticut Journal and New-Haven Post-Boy that they recently acquired new merchandise. William Sherman advertised a “compleat Assortment of English & India Goods” and a “general Assortment of Hard-Ware.” Thomas Gelstharp stocked a “Small Assortment of the neatest Silk, Thread, Cotton & Worsted HOSE” and other garments, while Daniel Lyman carried a “fresh Assortment of GOODS,” including nails, wines, shoes, and “sundry Articles, too tedious for Advertisement.”

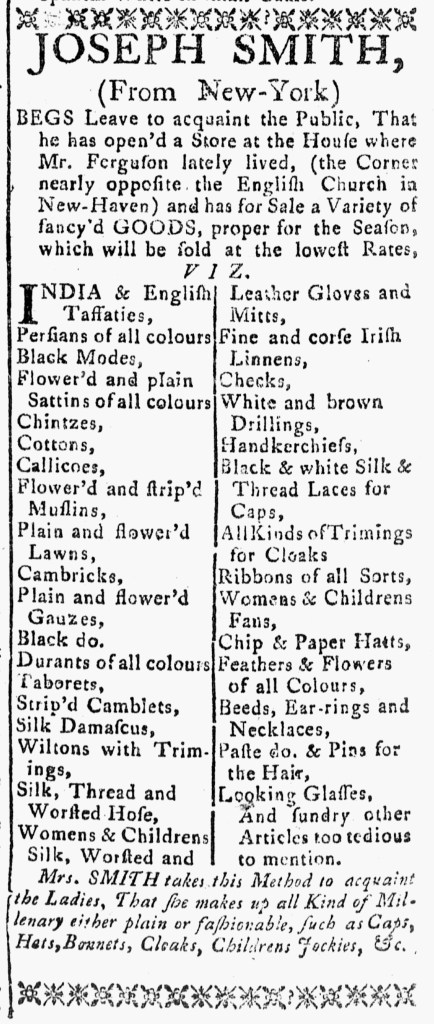

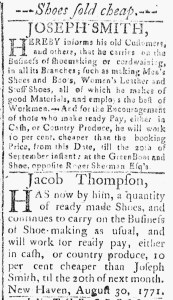

Joseph Smith promoted his own “fresh and neat Assortment of GOODS, suitable for the Season,” but, unlike Lyman, he did wish to provide a more complete catalog of his wares to entice prospective customers to visit his shop. His brief advertisement, however, ended with a note that “(The Particulars will be in our next.)” A more extensive advertisement did indeed appear in the May 28, 1773, edition of the Connecticut Journal, filling more than half a column and listing dozens of items.

What explained the note appended to Smith’s initial advertisement? Had his new merchandise “just come to Hand” so recently that he did not have an opportunity to compose a list of items in time to submit his advertisement to the printing office for the next edition of the Connecticut Journal? Had that been the case, he may have believed that a short notice with few details was better than no advertisement at all. When readers encountered the advertisements from Sherman, Gelstharp, and Lyman, they also saw Smith’s notice.

On the other hand, the printers, Thomas Green and Samuel Green, may have revised Smith’s advertisement and inserted the note about “The Particulars” appearing in the next issue because they did not have sufficient space to run all of the copy. They could have strategically selected which advertisement to truncate when they set type for the May 28 edition. In that case, how did they handle the accounting and customer service? Did the abbreviated version run gratis, the note about “The Particulars” intended for the advertiser rather than readers? Did Smith pay a reduced rate for it? Did the printers make any other effort to alert Smith that they would print his advertisement in its entirety but did not have enough space in the current issue?

Printers who published newspapers depended on revenue from advertising as much as revenue from subscriptions. In addition, they likely had more contact with most advertisers than they had with most subscribers, especially considering that advertisements usually ran for only three or four weeks. Renewing advertisements or placing new ones required contacting the printing office once again. Both resulted in additional entries in the ledgers. Printers likely had to exert more effort in managing their relationships with their advertisers than their relationships with their subscribers. The note at the end of Smith’s advertisement may have been part of the Greens’ effort to manage their relationship with a local shopkeeper they hoped would continue to place notices in their newspaper.