What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“This being the safest and most efficacious method of convincing the Ministry of Great-Britain of their errour.”

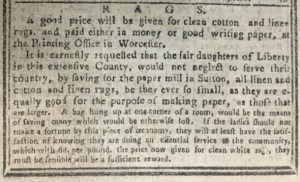

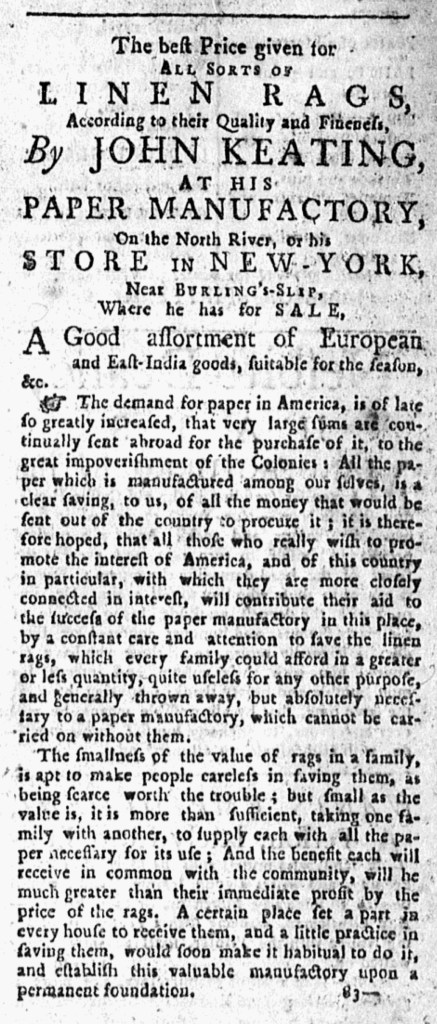

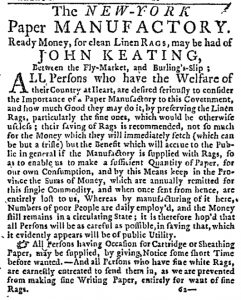

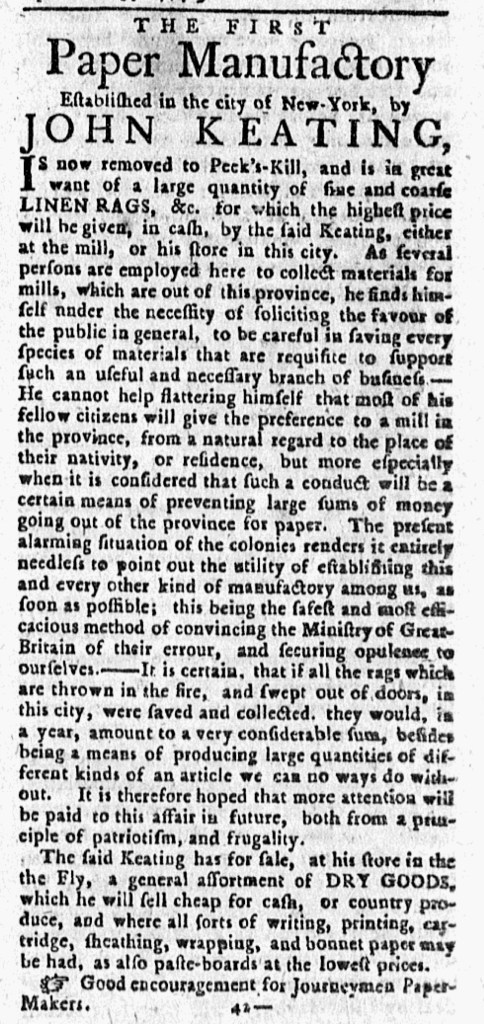

John Keating frequently advertised the “FIRST Paper Manufactory Established in the city of New-York” in the late 1760s and early 1770s. He often updated his advertisement, yet he incorporated familiar themes about patriotism and supporting the local economy. He also encouraged readers to save linen rags to make into paper, underscoring that they could play an important role in the production of paper made in the colonies as well as its consumption.

Such was the case in an advertisement in the supplement that accompanied the October 20, 1774, edition of the New-York Journal. Keating opened with an announcement that his enterprise “is in great want of a large quantity of fine and coarse LINEN RAGS.” He encouraged “the public in general, to be careful in saving every species of materials that are requisite to support such a useful and necessary branch of business.” In previous advertisements, he offered instructions for collecting and saving rags as part of the rituals of household management, entrusting women in particular with supplying the resources necessary for the operation of the local paper mill and, in the process, lauding the patriotic spirit of those who heeded his call. In this instance, he did not distinguish men and women, instead stating that when it came to choosing which paper to consume “that most of his fellow citizens will give the preference to a mill in the province … when it is considered that such a conduct will be a certain means of preventing large sums of money going out of the province.” In addition to supporting the local economy, Keating asserted that the “present alarming situation of the colonies renders it entirely needless to point out the utility of establishing this and every other kind of manufactory among us, as soon as possible.” Such a plan, he declared, was “the safest and most efficacious method of convincing the Ministry of Great-Britain of their error, and securing opulence to ourselves.” Keating effortlessly connected politics, commerce, and the livelihoods and good fortune of colonizers who benefited from domestic manufactures as alternatives to imported goods. He did so once again with a plea “that more attention will be paid to this affair in the future, both from a principle of patriotism, and frugality.” In so doing, Keating presented a multitude of reasons for readers to support American industry and buy American products as the imperial crisis intensified.