What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

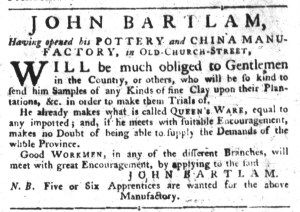

“He already makes what is called QUEEN’S WARE, equal to any imported.”

When Parliament imposed duties on certain goods imported into the American colonies in the late 1760s, colonists responded by adopting nonimportation agreements. They reasoned that they could practice politics via commerce, refusing to purchase all sorts of goods from Britain until Parliament repealed the duties on paper, glass, lead, paint, and tea. Concurrently, colonists sought to address a trade imbalance and strengthen local economies by encouraging the production and consumption of goods made in the colonies. They set about encouraging “domestic manufactures.” Newspaper editorials called on entrepreneurs to produce goods. Newspaper advertisements called on consumers to purchase those goods and, especially, to select them over imported alternatives.

It was in that context that John Bartlam “opened his POTTERY and CHINA MANUFACTORY” in Charleston in 1770. There he made and sold “what is called QUEEN’S WARE,” describing it as “equal to any imported.” Consumers did not have to sacrifice quality when they expressed their political principles in the marketplace. Bartlam was ambitious. He proposed that he could “supply the Demands of the whole Province” if given the opportunity by consumers in South Carolina. That required that consumers recognize their duty to give “suitable Encouragement” to entrepreneurs who produced “domestic manufactures.” Bartlam offered another means for colonists to support both his enterprise and, by extension the American cause. He requested that “Gentlemen in the Country, or others” send him “Samples of fine Clay upon their Plantations” so he could identify sources for the materials he needed to expand production. Production and consumption, Bartlam suggested, were not the only means of encouraging “domestic manufactures.”

In addition to providing an alternative to imported goods, Bartlam’s business also provided training and employment for colonists. In his advertisement he announced that he needed five or six apprentices. He also had openings for “Good WORKMEN, in any of the different Branches” associated with producing pottery and china.

Bartlam did not explicitly invoke the Townshend Acts or nonimportation agreements in his advertisement that ran in the November 22, 1770, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette, but that was hardly necessary. News items elsewhere in the issue discussed the “General Resolutions” adopted by inhabitants of the colony. Other advertisements condemned “NON-SUBSCRIBERS” who refused to abide by the nonimportation agreements. Bartlam did not need to rehearse the history of the dispute between colonists and Parliament. Readers, both prospective customers and potential suppliers of materials, already understood the politics embedded in Bartlam’s advertisement.