What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Contains as much news, as many Political Essays, as any in America.”

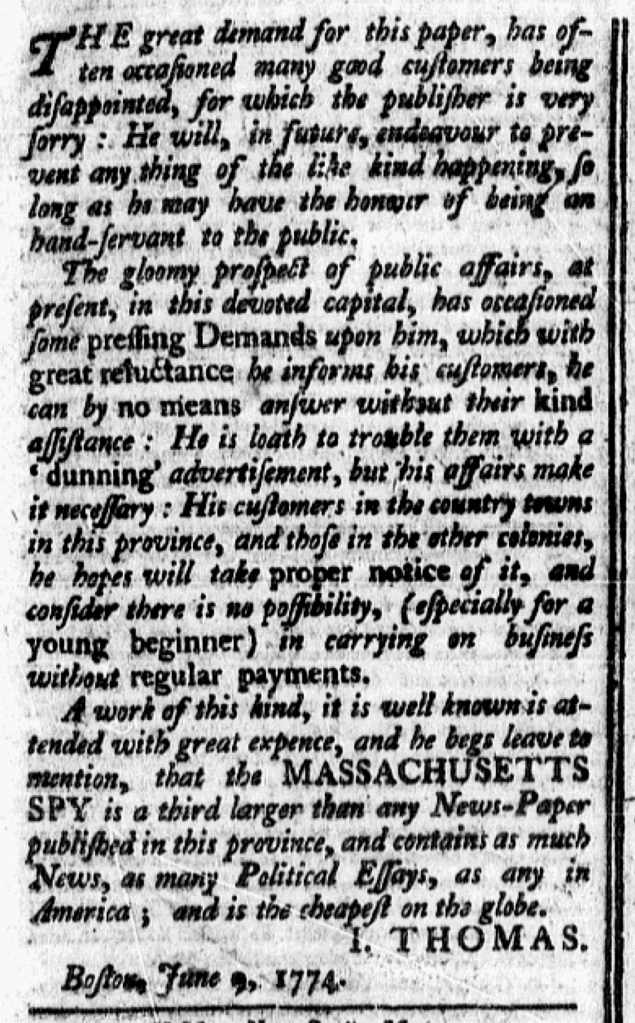

Printers and other entrepreneurs often published notices calling on customers and associates to settle accounts. Isaiah Thomas, the printer of the Massachusetts Spy, did so in June 1774, though he confessed that he “is loath to trouble them with a ‘dunning’ advertisement.” Still, “his affairs make it necessary.” Many printers threatened legal action against those who did not submit payment, but Thomas opted for a different strategy. His “‘dunning’ advertisement” focused primarily on the service to the public he provided in publishing the Massachusetts Spy, especially considering the “gloomy prospect of public affairs, at present.” Readers knew, of course, that he referred to the Boston Port Act that initiated a blockade of the harbor and halted trade at the beginning of the month as well as a series of troubling events over the past decade.

Zechariah Fowle and Thomas commended publishing the Massachusetts Spy in July 1770, four months after the Boston Massacre. At the age of twenty-one, Thomas became the sole proprietor just a few months later. In the four years that the newspaper had been published, the young printer sought to establish its reputation in Boston and beyond. When he asked subscribers to pay what they owed, he underscored that “the MASSACHUSETTS SPY is a third larger than any News-Paper published in this province.” That distinguished it from the Boston Evening-Post, the Boston-Gazette, the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy, and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter as well as the Essex Gazette, published in Salem, and the Essex Journal, published in Newburyport. At the time, no other city or colony had as many newspapers, which meant that Thomas faced significant competition for subscribers and advertisers. Furthermore, Thomas’s newspaper “contains as much News, [and] as many Political Essays, as any in America,” making it a valuable resource for readers far and wide. Thomas also asserted that the Massachusetts Spy “is the cheapest on the globe,” making it a good value that merited support (and payment) from readers.

In return for “the honour of being an hand-servant to the public,” Thomas requested the “kind assistance” of his customers. He asked that they “take proper notice” of his appeal, warning that “there is no possibility … in carrying on business without regular payments.” The June 9 edition of his newspaper featured extensive coverage of the “PROCEEDINGS in the HOUSE of COMMONS” from April, including an “Authentic account of Tuesday’s Debate on the Motion for repealing the Tea-Duty in America,” and editorials “To the FREE and BRAVE AMERICANS” from “AN AMERICAN” and “To the ADRESSERS of the late Governor HUTCHINSON” from “A MODERATE MAN.” Thomas compiled and circulated such news and opinion as a service, but could not afford to continue that endeavor without receiving subscription fees from his customers. Rather than an explicit threat to take them to court to force them to pay what they owed, Thomas made a much more subtle insinuation about what they would lose if they did not settle accounts. By his accounting, no other newspaper compared to the Massachusetts Spy.