What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“His Carriages, for twelve Years has never been overset, nor any Passengers met with any Hurt.”

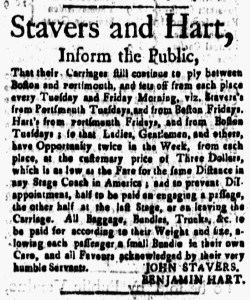

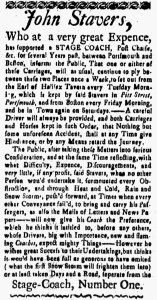

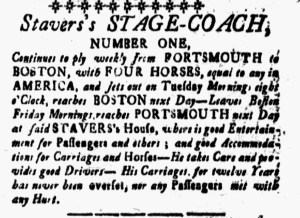

John Stavers marketed experience when he advertised his stagecoach service between Portsmouth and Boston in the January 28, 1774, edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette, just as he had done in previous advertisements. He proclaimed that “His Carriages, for twelve Years has never been overset, nor any Passengers met with any Hurt.” That was quite the safety record. The proprietor even invoked his experience in the name of his business, “Stavers’s STAGE-COACH, NUMBER ONE.” That was not merely a ranking but also a reference to the fact that he had operated service between Portsmouth and Boston longer than any of his competitors.

Stavers also promoted the quality of that service, declaring that “FOUR HORSES, equal to any in AMERICA,” pulled the coach. In addition, he “takes Care and provides good Drivers,” selecting only the best employees to represent the business he operated for more than a decade. At the terminus in Portsmouth, Stavers ran an inn and tavern, where he provided “good Entertainment for Passengers and others” as well as “good Accommodations for Carriages and Horses.” Whether or not they rode his stagecoach, Stavers offered hospitality to travelers who visited Portsmouth. For those who boarded in Boston or along the way to Portsmouth, he offered convenient lodging.

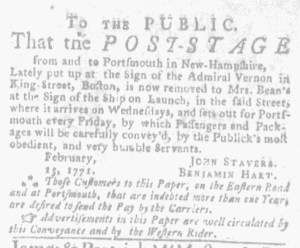

As was typical in advertisements for stagecoaches and ferries, Stavers provided a schedule so prospective clients could plan accordingly. His service made the trip to Boston and back once a week. “NUMBER ONE” departed Portsmouth at eight o’clock on Tuesday mornings and arrived in Boston the next day. Passengers who planned to return to Portsmouth on the next trip had Wednesday evening and the entire day on Thursday to conduct business in Boston before the stagecoach left again on Friday morning and reached Portsmouth on Saturday.

Other operators also established service between Portsmouth and Boston, but Stavers most consistently advertised in the New-Hampshire Gazette and newspapers published in New England’s largest port city. For instance, the February 3 edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter included the same advertisement with an additional nota bene to inform “Such as want a Passage from Boston, are desired to apply to Mrs. Bean’s in King-Street.” Perhaps savvy advertising played a role in Stavers’s enterprise achieving such longevity.