What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

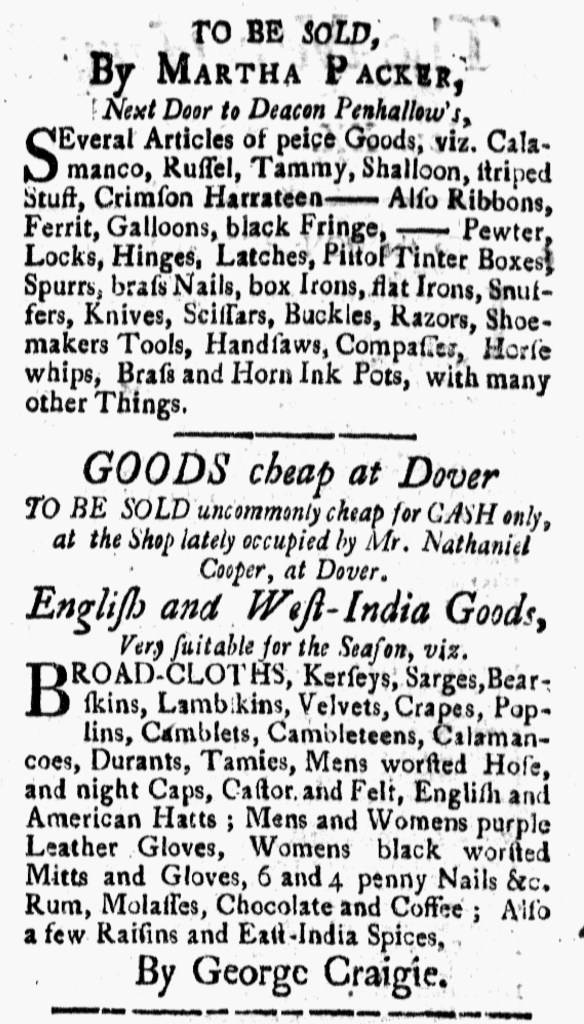

“English and West-India Goods, Very suitable for the Season.”

In January 1776, Martha Packer ran a shop “Next Door to Deacon Penhallow’s” in Portsmouth. According to her advertisement in the January 9 edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette, she stocked several kinds of textiles, ribbons, hardware, horse whips, ink pots, and “many other things.” Immediately below her notice, George Craigie promoted “GOODS cheap at Dover TO BE SOLD uncommonly cheap.” His inventory of “English and West-India Goods” included textiles, hats, gloves, rum, molasses, chocolate, and coffee. Both advertisements looked much like those that ran in the New-Hampshire Gazette and other colonial newspapers before the Revolutionary War began.

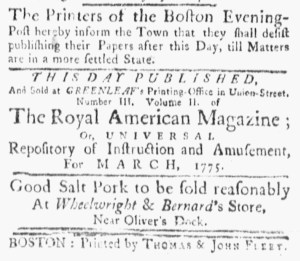

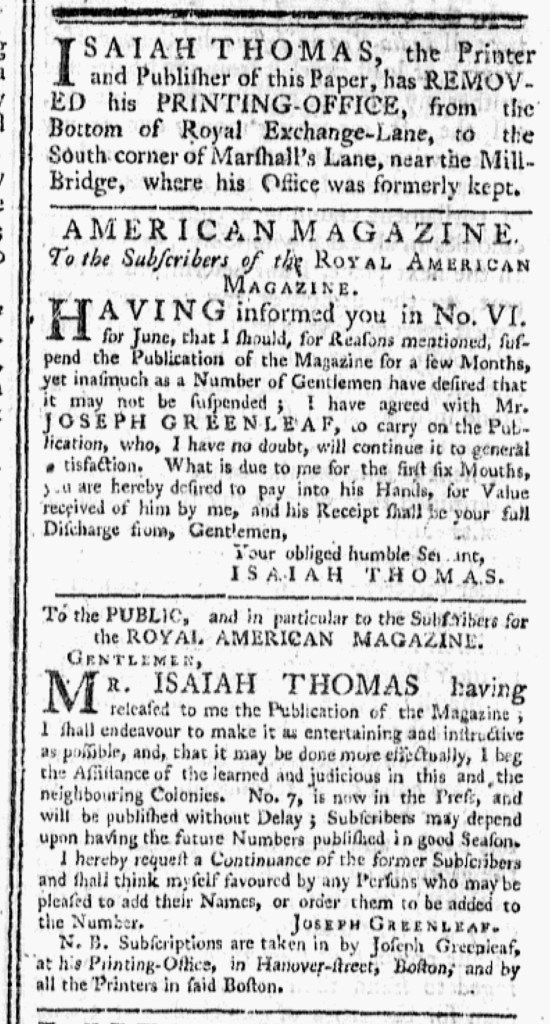

Although those advertisements looked like business as usual, that was far from the case for the New-Hampshire Gazette. Daniel Fowle, the printer, experienced disruptions in his supply of paper and, for a brief period in the fall of 1775, moved the press to Greenland when rumors circulated about a possible British attack on Portsmouth. The issue that carried Packer’s and Craigie’s advertisements was the last one published for more than two years. Edward Connery Lathem gives a brief overview in his Chronological Tables of American Newspapers, 1690-1820, noting that the New-Hampshire Gazette was suspended on January 9, 1776, and resumed on June 16, 1778.[1] In his History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820, Clarence S. Brigham offers a more complete overview.[2] He states that the January 9, 1776, issue featured “a communication strongly attacking independency.” In turn, on January 17, “the New Hampshire House of Representatives ‘Voted that Daniel Fowle Esqr the Supposed Printer of said Paper be forthwith Sent for and ordered to Appear before this house and give an account of the Author of said Piece, and further to answer for his Printing said piece.’” Brigham does not, however, indicate that displeasure with that editorial caused the suspension. For his part, Isaiah Thomas, a Patriot printer and contemporary of Fowle, thought that the New-Hampshire Gazette “was not remarkable in its political features; but its general complexion was favorable to the cause of the country” when he discussed the newspaper in his History of Printing in America in 1810.[3] Neither Thomas nor Brigham reported why Fowle suspended the New-Hampshire Gazette. It may have simply been the difficulty of continuing the newspaper during the war. Whatever the reason, the New-Hampshire Gazette, which has sometimes been disproportionately represented in this project, will disappear from the Adverts 250 Project for a while, but it will not be long before the project features advertisements from other newspapers established in New-Hampshire during the war. For instance, Benjamin Dearborn commenced publishing the Freeman’s Journal, or New-Hampshire Gazette in Portsmouth on May 25, 1776.

**********

[1] Edward Connery Lathem, Chronological Tables of American Newspapers, 1690-1802 (American Antiquarian Society and Barre Publishers, 1972), 11.

[2] Clarence S. Brigham, History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820 (American Antiquarian Society, 1947), 471-473.

[3] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (1810; Weathervane Books, 1970), 335.