What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“At this critical and alarming juncture … set up the business of REED-MAKING.”

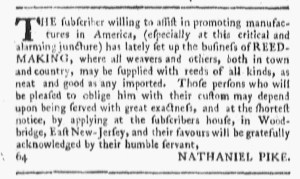

Nathaniel Pike testified that he wished to do his part to support the American cause in an advertisement in the July 14, 1774, edition of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer. He informed the public that he was “willing to assist in promoting manufacturers in America, (especially at this critical and alarming juncture)” and, accordingly, “lately set up the business of REED-MAKING.” Eighteenth-century readers familiar with weaving knew that reeds were the “part of a loom consisting of a set of evenly spaced wires known as dents (originally slender pieces of reed or cane) fastened between two parallel horizontal bars used for separating, or determining the spacing between, the warp threads, and for beating the weft into place.”[1] Pike pledged that “weavers and others, both in town and country, may be supplied with reeds of all kinds, as neat and good as any imported.”

Although Pike did not name the Boston Port Act or any of the other Coercive Acts passed by Parliament in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party, readers certainly understood the context for his reference to “this critical and alarming juncture.” From New England to Georgia, colonizers discussed how to respond, many of them advocating for a new round of nonimportation agreements like the ones enacted in response to the Stamp Act and the duties imposed on certain goods in the Townshend Acts. That meant that “domestic manufactures” or goods produced in the colonies would become important alternatives to imported goods. Pike offered his own product made in the colonies, those reeds that matched imported ones in quality, yet his enterprise also facilitated greater production of textiles in the colonies. Every stage of producing cloth took on greater significance in the face of boycotting fabrics imported from England, from farmers raising sheep for their wool to women participating in spinning bees that put their patriotism on display to consumers choosing and wearing homespun cloth out of allegiance to their political principles. By supplying weavers with reeds for their looms, Pike served a vital role in protests against the abuses perpetrated by Parliament. He expected that current events would help in marketing his product.

**********

[1] Oxford English Dictionary, II.11.a.