Who was the subject of an advertisement in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“An English servant man … intended to Boston to general Gage, who he understood would protect all servants who came to him.”

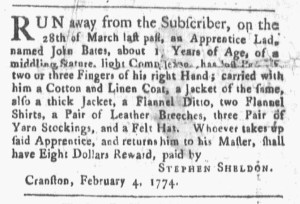

William Allein of Lower Marlborough in Calvert County turned to the Maryland Gazette to seek assistance in recovering an enslaved man and an indentured servant in the summer of 1775. He ran two advertisements in the July 13 edition, one concerning Mial, an enslaved man who became a fugitive for freedom at the beginning of May, and Slude, an “English servant man” who “WENT away” in early July. Allein expected newspaper readers to observe strangers to assess whether they matched the descriptions he published, offering rewards to those who participated in securing Mial and Slude and returning them to him.

Allein gave a physical description of Slude, including recent injuries (“his thumb and middle finger on his left hand fresh cut” and “a sore heel which occasions him to limp at times”) that could make him easier to recognize, and detailed the clothing that Slude wore or took with him. His “North country dialect” also distinguished the indentured servant. According to Allein, Slude was “by trade a sawyer, though he pretends to be a gardener and weaver.” He would engage in other subterfuge as well, changing his name and traveling by night to avoid detection.

Compared to many of his counterparts who placed other advertisements for runaway indentured servants, apprentices, and convict servants and enslaved people who liberated themselves, Allein was well informed about where Mial and Slude were likely headed. “I have heard that [Mial] proposed going towards Alexandria in Virginia,” Allein declared. As for Slude, “I understand that … he intended to Boston to general Gage, who he understood would protect all servants who came to him.” Current events influenced Slude when he planned the route for making his escape; he apparently relied on rumors, hoping for their veracity. Word of the battles at Lexington and Concord and the ensuing siege of Boston quickly spread throughout the colonies, as did news of the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Yet not all the news was always accurate, not even the accounts printed in newspapers. The confusion created openings for men like Slude to embrace the reports that they wanted to believe. In the end, however, Mial may have been more successful in eluding Allein than Slude was. The advertisement describing Mial ran for many weeks, but the notice about Slude appeared only once. The indentured servant heading to Boston may have been recognized and captured shortly after it appeared, prompting Allein to discontinue the advertisement. If Mial made it to Virginia and managed to avoid capture until November, he might have joined Lord Dunmore, the royal governor, when he issued a proclamation that offered freedom to enslaved people and indentured servants “appertaining to Rebels” if they joined “His MAJESTY’s Troops” in “reducing this Colony to a proper Sense of their Duty.”