What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Forgive my Error [and] restore me to their Favour and Friendship.”

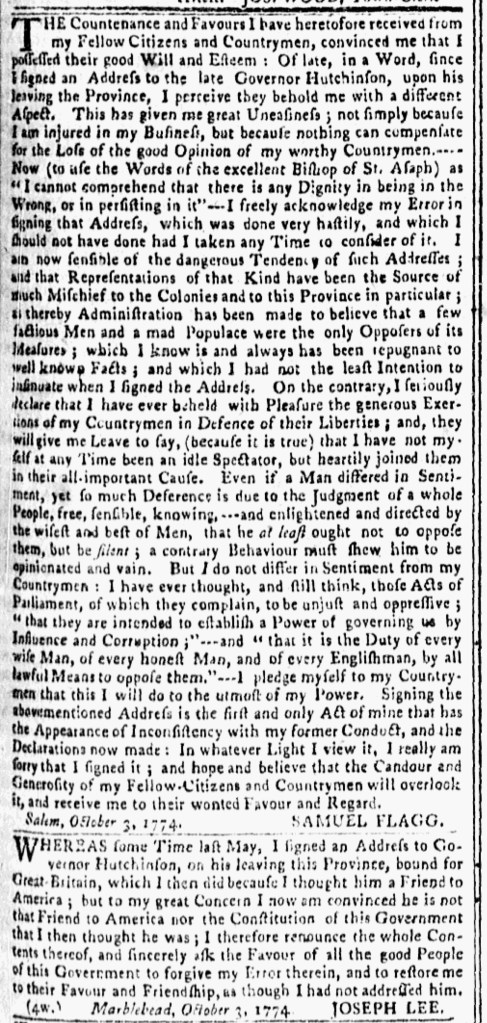

Samuel Flagg of Salem and Joseph Lee of Marblehead needed to do damage control and rehabilitate their reputations after signing “an Address to Governor Hutchinson, on his leaving this Province” in May 1774. Like Thomas Kidder had done in July, they took to the public prints to confess their error and beg for the forgiveness of their friends and neighbors who believed they did not support the American cause. The reaction they experienced became so overwhelming that they recanted a position that they claimed they never firmly held. Lee, for instance, stated that he signed the address because at the time he “thought [Hutchinson] a Friend to America,” yet he had since reconsidered. He expressed “great Concern” while confessing that “I am now convinced he is not that Friend to America nor the Constitution of this Government that I then thought he was.” To that end, Lee renounced the entire address and “sincerely ask[ed] the Favour of all the good People of this Government to forgive my Error therein, and to restore me to their Favour and Friendship.” His plea, dated October 3, first appeared in the October 4 edition of the Essex Gazette, with a notation that it would run for four weeks. Rather than submitting a letter to the printer that might get printed once, Lee paid to run an advertisement that would present his story and his apology to readers multiple times.

Lee’s notice was brief compared to the one that Flagg inserted on the same day. He had formerly been in good standing in the community, having the “good Will and Esteem” of his “Fellow Citizens and Countrymen,” but perceived “they behold me with a different aspect” after he signed an address in honor of the Governor Hutchinson upon his return to England. Flagg confessed that this “has given me great Uneasiness; not simply because I am injured in my Business, but because nothing can compensate for the Loss of the good Opinion of my worthy Countrymen.” Flagg acknowledged that his livelihood had suffered; apparently customers refused to shop at his store in Salem. Yet participating in the marketplace was not the only or even the primary reason that Flagg wished to correct the record. He desired the “Favour and Regard” that he had once enjoyed in relationships with other colonizers, plus he wanted to assure the public that he indeed supported the patriot cause. He admitted his error while disavowing the address as “the Source of much Mischief to the Colonies and to this Province in particular,” but did not end there. “I seriously declare,” he wrote, “that I have ever beheld with Pleasure the generous Exertions of my Countrymen in Defence of their Liberties.” Furthermore, Flagg claimed that “I have note myself at any Time been an idle Spectator, but heartily joined them in their all-important Cause.” In his advertisement for an “Assortment of ENGLISH and INDIA GOODS” on the next page, he indicated that he “is determined not to import any more Goods at Present,” signaling his support for nonimportation agreements as a means of protesting the Coercive Acts.

Beyond his confession and apology, Flagg incorporated an editorial into his advertisement seeking forgiveness from his “Fellow Citizens and Countrymen.” He asserted, “I do not differ in Sentiment from my Countrymen; I have ever thought, and still think, those Acts of Parliament, of which they complain, to be unjust and oppressive.” To demonstrate that point, he inserted quotations that made familiar arguments: “‘that they are intended to establish a Power of governing us by Influence and Corruption’” and “‘that it is the Duty of every wise Man, of every honest Man, and of every Englishman, by all lawful Means to oppose them.’” Flagg thus had a duty to fulfill, prompting him to “pledge myself to my Countrymen that this I will do to the utmost of my Power.” He reiterated that he regretted signing the “abovementioned Address,” insisting that it was “the first and only Act of mine that has the Appearance of Inconsistency with my former Conduct, and the Declarations now made.” He apologized once again, requesting the “Candour and Generosity” of others in overlooking the entire incident.

Signing the address to Governor Hutchinson had been a lapse in judgment; at least that was how some of those who signed it depicted their actions when they repeatedly encountered hostile reactions. Both Flagg and Lee sought to remedy the damage done to their reputations by placing advertisements in which they confessed their error. Flagg did even more: he spilled a lot of ink in support of the American cause, hoping that doing so would convince the public of his sincerity and return him to their good graces. News and editorials could not contain the politics of the period. Instead, advertisements became sites for participating in debates and controversies as the imperial crisis intensified in 1774.