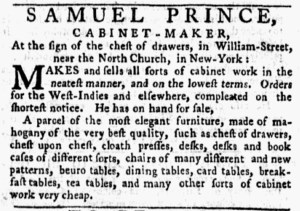

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Orders for the West-Indies and elsewhere, compleated on the shortest notice.”

Samuel Prince, a cabinetmaker, produced furniture in his workshop “At the sign of the chest of drawers, in William-Street, near the North Church, in New-York” in the 1770s. In February 1775, he took to the pages of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury to promote a “parcel of the most elegant furniture, made of mahogany,” imported from the West Indies, “of the very best quality.” In addition to the “chest of drawers, … desks and book cases of different sorts, [and] chairs of many different and new patterns” that he had on hand, Prince made “all sorts of cabinet work in the neatest manner, and on the lowest terms.”

While he certainly sought customers in New York, he also indicated that he accepted “Orders for the West-Indies and elsewhere” and shipped the furniture to his clients. That Prince addressed prospective customers in the West Indies testified to the circulation of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury and other colonial newspapers. The cabinetmaker had a reasonable expectation that prospective customers in faraway places would see his advertisement.

Prince promised that he “completed” orders “on the shortest notice, an appeal with additional significance since the Continental Association went into effect. Devised by the First Continental Congress, that nonimportation, nonconsumption, and nonexportation agreement was designed to use commerce as leverage for convincing Parliament to repeal the Coercive Acts. The fourth article specified that the “earnest Desire we have not to injure our Fellow Subjects in Great Britain, Ireland, or the West Indies, induces us to suspend a Non-exportation until the tenth Day of September 1775.” If Parliament did not take satisfactory action by that time, “we will not, directly or indirectly, export any Merchandise, or Commodity whatsoever, to Great Britain, Ireland, or the West Indies.” In other words, Prince and prospective clients in the West Indies had a short window of opportunity for placing orders, producing the furniture, and shipping it. Prince did not violate the provisions of the Continental Association, but he likely had that looming deadline in mind when he pledged to fill orders “on the shortest notice.”