GUEST CURATOR: Colin Wren

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

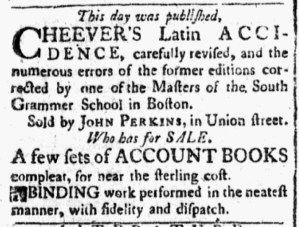

“CHEEVER’S Latin ACCIDENCE, carefully revised.”

Ezekiel Cheever, the author of A Short Introduction to the Latin Tongue, was a Puritan who migrated to New England in 1637. He originally settled in Connecticut before moving to Massachusetts to teach Latin and grammar in the public schools. In 1670 he took the position of Master of the Boston Latin Grammar School which he held until his death in 1708. During his life he was widely loved by his students despite his strict reputation. Under his leadership the school became regarded as one of the best in the colonies and his students included men such as the poet Michael Wigglesworth, Governor Johnathan Belcher, and Judge Samuel Sewall. One year after his death, one of Cheever’s students compiled his teaching notes into a book and published Cheever’s Accidence in 1709. The book was exceedingly popular and became the unofficial standard textbook for teaching Latin grammar in America. In all, twenty-three editions of the book were published, the last of which was published in 1838. While “Latin ACCIDENCE,” as the book was called in this advertisement, was written to teach students Latin, it also taught them the basics of English grammar and helped to formalize definitions that are still taught in schools today.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Colin selected an advertisement for the fifteenth edition of Ezekiel Cheever’s Short Introduction to the Latin Tongue. Two variants of that edition hit the market in 1771. In one, the imprint stated, “Printed and sold by Isaiah Thomas, in Union-Street.” In the other, the imprint declared, “Printed by Isaiah Thomas, for John Perkins, on Union-Street.” According to the catalogers at the American Antiquarian Society, only the imprints differed between the two volumes. Perkins most likely placed the advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy since it advised prospective customers that he sold the textbook, as well as a “few sets of ACCOUNT BOOKS,” but did not mention Thomas.

What prompted Thomas to produce variant imprints for the fifteenth edition? Did Perkins pay to publish only a certain number to carry at his shop, assuming the risk for those copies but not for any others? If so, did he and Thomas agree in advance that the printer would produce additional copies that omitted Perkins’s name from the imprint? Or did production take place in the opposite order? Perhaps Thomas initiated the project, but Perkins recognized an opportunity to profit from a new edition, one with significant improvements. The advertisement did underscore that the volume had been “carefully revised, and the numerous errors of the former editions corrected by one of the Masters of the South Grammer School in Boston.”

Whatever the order of publication of the variants, Perkins turned to Thomas when he set about marketing the book, inserting an advertisement in the newspaper that Thomas published. Did Perkins have to pay for that advertisement? Or was advertising part of a more extensive agreement? Given that Perkins also promoted “BINDING work performed in the neatest manner, with fidelity and dispatch,” the two entrepreneurs, fellow members of the book trades who possessed different skills, may have negotiated several in-kind exchanges that went beyond publishing Cheever’s “Latin ACCIDENCE.”