What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Removed next door to the white corner house … a dial plate over the window.”

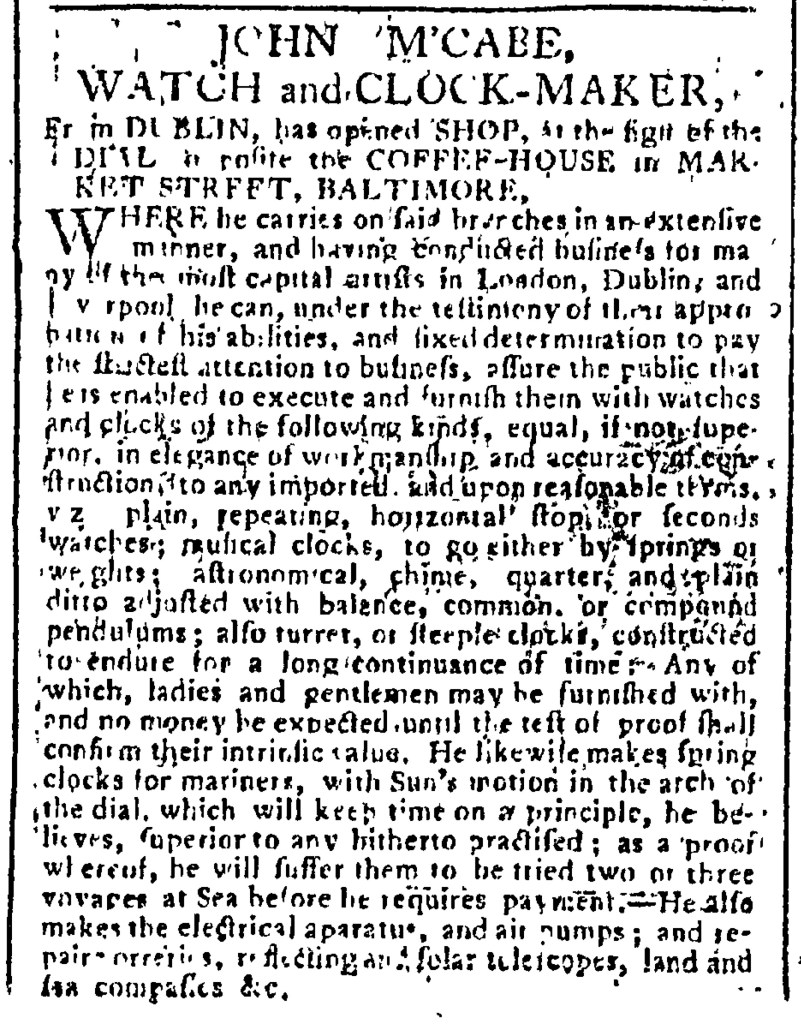

John Simnet, a cantankerous watchmaker who frequently advertised in New York’s newspapers in the early 1770s, once again took to the pages of the New-York Journal in the summer of 1775. In this notice, he announced that he “continues to repair and clean old watches … and sells new watches.” He took a neutral tone in that notice compared to the derogatory declarations he sometimes made about his competitors in other advertisements. Simnet did state that he cleaned and repaired watches “much cheaper and better than is usual,” comparing the price and quality of his services to those offered by other watchmakers, but he did not denounce any competitors by name or launch into a diatribe about the general incompetence of those who followed an occupation he often claimed as solely his own. He also described himself as “one of the first who brought this curious and useful manufacture to perfection,” but limited that comment to promoting his own work rather than denigrating other watchmakers.

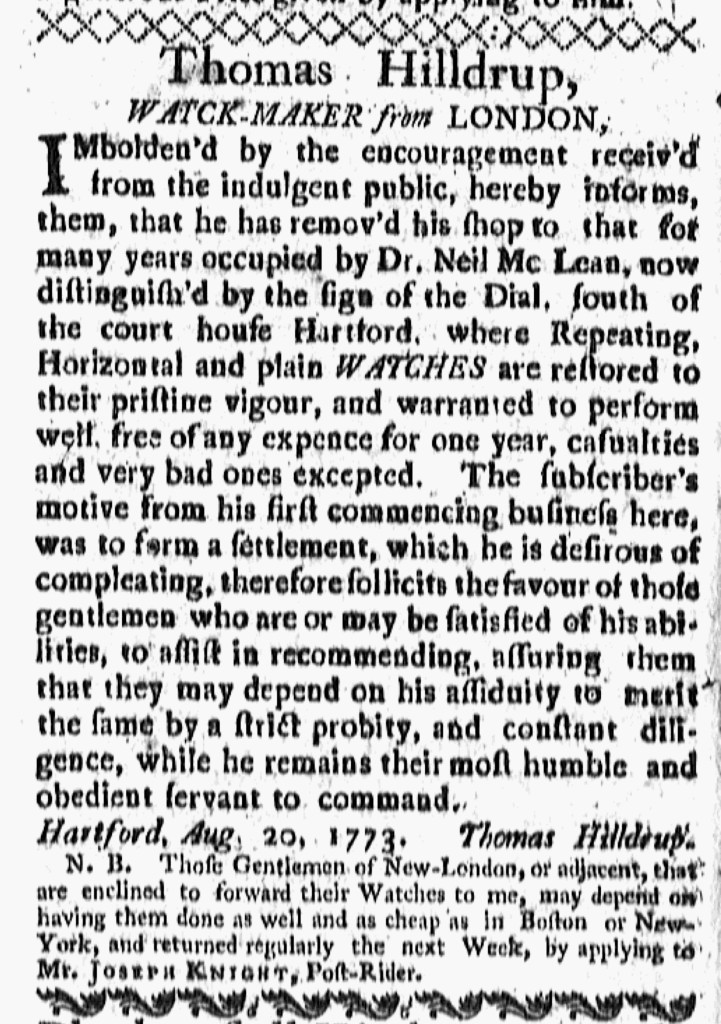

Perhaps Simnet was more interested in drawing attention to his new location. He moved from a shop “at the Dial, next Beekman’s Slip, in Queen Street” to a shop “next door to the white corner house, New-York, opposite to the Coffee-House, and lower corner of the bridge.” Detailed directions were necessary. Neither New York nor any other town had standardized street numbers in the 1770s, though some of the largest port cities would begin assigning them by the end of the century. Sinnet resorted to landmarks to direct customers to his shop. Like many other entrepreneurs, he also marked his location with a device that represented his business, “a dial plate over the window.” It may have been the same “Dial” that had adorned his previous location. If Simnet did transfer the “dial plate” from one shop to another, he maintained a consistent visual image for customers and others to associate with his business. Other entrepreneurs who placed advertisements in the July 6, 1775, edition of the New-York Journal also used images to mark their locations, including James Wallace, a lacemaker and tailor “At the SIGN of the HOOD,” and William Pearson, a clock- and watchmaker “At the Dial, in HANOVER-SQUARE.” That a competitor displayed a dial made Simnet’s elaborate directions imperative. He did not want prospective customers stopping by another shop by mistake.