What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Forward their Watches to me … by applying to Mr. JOSEPH KNIGHT, Post-Rider.”

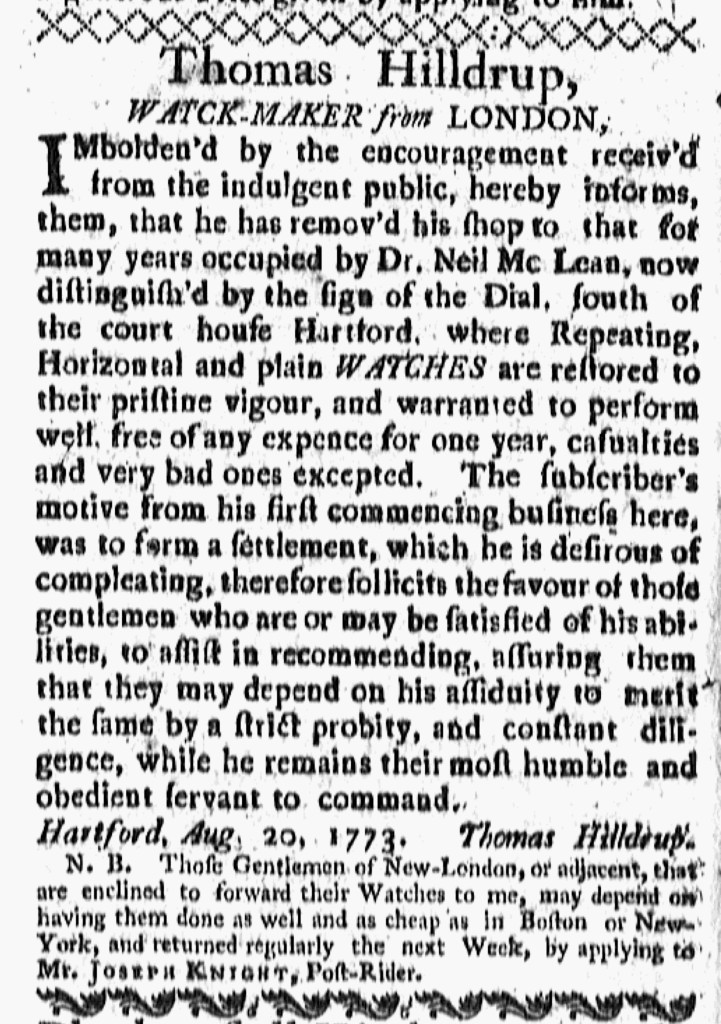

Thomas Hilldrup, “WATCK-MAKER from LONDON,” continued his advertising campaign in the fall of 1773. Having settled in Hartford the previous year, he first set about cultivating a local clientele with advertisements in the Connecticut Courant, that town’s only newspaper. Over time, he expanded his marketing efforts to include the Connecticut Journal and New-Haven Post-Boy and the New-London Gazette. That meant that he advertised in every newspaper published in Connecticut at the time. In an advertisement that ran for several months, Hilldrup declared that he had been “IMbolden’d by the encouragement receiv’d from the indulgent public” to move to a new location “now distinguish’d by the sign of the Dial.” In other words, business had been good, customers had entrusted their watches to the enterprising newcomer for cleaning and repairs, and that demand for his services meant that others should engage him as well.

To that end, Hilldrup presented instructions for sending watches to his shop. He appended a nota bene to his advertisement in the New-London Gazette, stating that the “Gentlemen of New-London, or adjacent, that are inclined to forward their Watches to me, may depend on having them done as well and as cheap as in Boston or New-York.” In addition, Hilldrup offered speedy service, promising to return watches “the next Week.” Clients could take advantage of these services, including a one-year warranty, “by applying to Mr. JOSEPH KNIGHT, Post-Rider.” Knight did far more than deliver letters and newspapers from town to town. He also contracted with various entrepreneurs to facilitate their businesses. In addition to transporting watches for Hilldrup, Knight also sold “An ORATION, Upon the BEAUTIES of LIBERTY,” a popular political tract, in collaboration with Timothy Green, the printer of the New-London Gazette, and Nathan Bushnell, Jr., another post rider. In forming a partnership with Knight, Hilldrup established an infrastructure for transporting watches to and from his shop, one that he could promote to prospective clients who might have otherwise been anxious about sending their watches over long distances. Enlisting an associate already familiar in several towns in Connecticut, Hilldrup marketed an approved and secure method for sending watches to him to restore “to their pristine vigour.”