What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He proposes … to apply himself to writing Conveyances of all Kinds.”

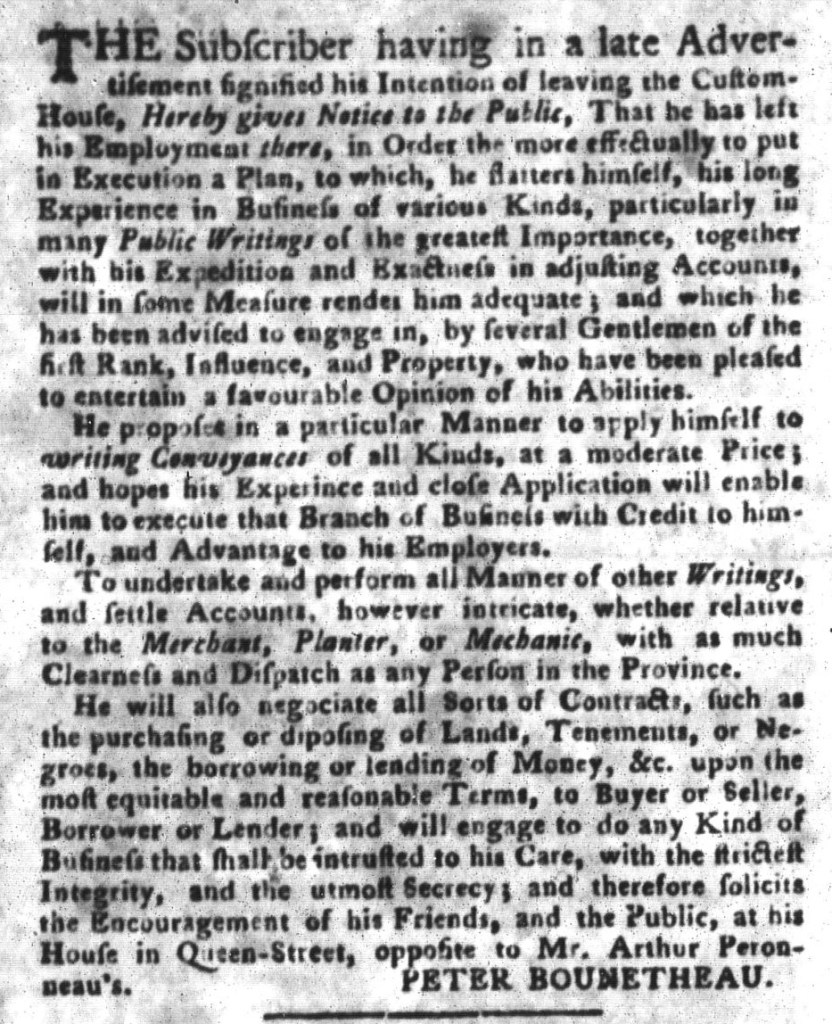

On the eve of the American Revolution, Peter Bounetheau left his job at the custom house in Charleston and established his own business for “writing Conveyances of all Kinds” and negotiating “all Sort of Contracts, such as the purchasing or disposing of Lands, Tenements, or Negroes [and] the borrowing or lending of Money.” He claimed that he had done so on the advice of “several Gentlemen of the first Rank, Influence, and Property, who have been pleased to entertain a favourable Opinion of his Abilities.” In addition to that endorsement, he emphasized “his long Experience in Business of various Kinds, particularly in many Public Writings of the greatest Importance, together with his Expedition and Exactness in adjusting Accounts.”

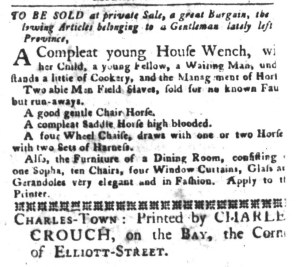

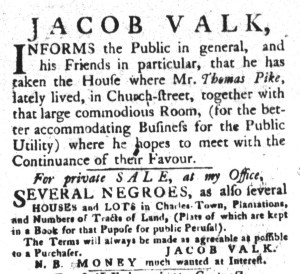

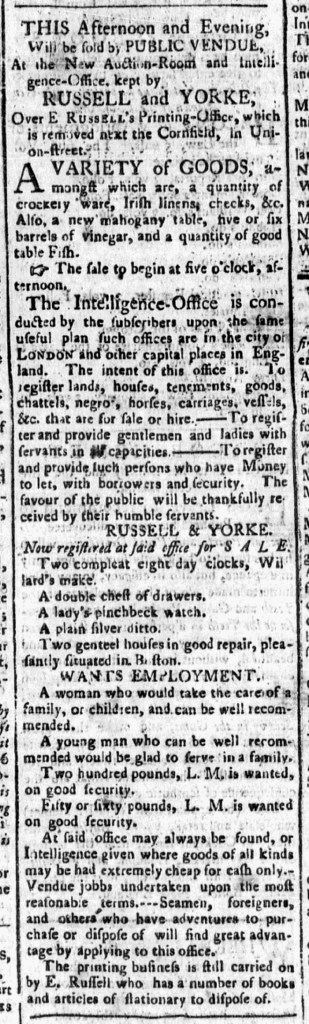

By the time his advertisement ran in the March 7, 1775, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, Bounetheau had been in business for several months. He had established himself well enough to attract clients that accounted for twelve other advertisements of various lengths on the same page. A couple concerned real estate and a couple hawked commodities like mustard and olives, yet most of them offered enslaved people for sale. Six of those advertisements enumerated three enslaved men, ten enslaved women, and six enslaved women that Bounetheau sought to sell on behalf of others. A seventh advertisement listed “Several NEGROES,” but did not specify how many beyond “a complete boatman and jobbing carpenter” and “a complete washer and ironer.” The others were “field slaves.”

Bounetheau’s enterprise meant good business for Charles Crouch, the printer of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. Week after week, the broker placed multiple advertisements, representing significant revenues for the printing office. In the March 7 edition, his notices filled an entire column and nearly half of another out of twelve total columns in a standard issue of four pages consisting of three columns each. That meant that Bounetheau generating ten percent of the content. Another broker, Philip Henry, inserted fifteen advertisements that occupied the same amount of space, though he focused more on real estate than enslaved people. Still, he offered “TWENTY-TWO young and healthy NEGROES, that have been used to a Plantation” in one notice and “ELEVEN NEGROES, chiefly Country born” in another. These brokerage firms likely increased the number of advertisements that ran in the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal and other newspapers published in Charleston in the 1770s. Such endeavors included greater dissemination of advertisements that contributed to perpetuating the slave trade.