What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

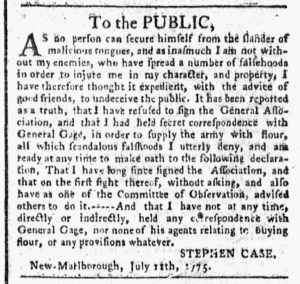

“I have not at any time, directly or indirectly, held any correspondence with General Gage.”

Stephen Case of New Marlborough, Massachusetts, needed to set the record straight. To do so, he placed a notice “To the PUBLIC” in the July 17, 1775, edition of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury. The stakes were too high to let unsubstantiated rumors go unanswered.

“As no person can secure himself from the slander of malicious tongues, and as inasmuch I am not without my enemies, who have spread a number of falsehoods in order to injure me in my character, and property,” Case asserted, “I have therefore thought it expedient, with the advice of good friends, to undeceive the public.” Even readers who had never heard of case likely found this introduction intriguing and wanted to learn more. “It has been reported as a truth,” Case continued, “that I have refused to sign the General Association,” the nonimportation agreement devised by the First Continental Congress in response to the Coercive Acts. Even worse, gossip spread that Case “held secret correspondence with General Gage, in order to supply the army with flour.” Gage simultaneously served as governor of Massachusetts and commander of the British regulars involved in the battles at Lexington and Concord, the siege of Boston, and the Battle of Bunker Hill. Such allegations against Case made him an enemy to the American cause and no doubt unpopular among many of his neighbors and associates.

Case strenuously objected. He denied the “scandalous falshoods” and was “ready at any time to make oath” about them. As far as the nonimportation agreement was concerned, he had “long since signed the Association, and [did so] on the first sight thereof, without asking” or prompting from others, “and also have as one of the Committee of Observation advised others to do it.” When it came to the other accusations, Case proclaimed, “I have not at any time, directly or indirectly, held any correspondence with General Gage, nor none of his agents relating to buying flour, or any provisions whatever.”

To deliver this message “To the PUBLIC,” Case purchased advertising space in a newspaper that circulated in western Massachusetts. The printer served as editor when it came to news items, letters, and other content, yet provided a forum for advertisers to publish their own news about current events. Case attempted to take advantage of such access to the public prints to repair the damage to his reputation, but perhaps too much damage had been done. Four months later he placed another advertisement in the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury (and the New-York Journal and Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer) that offered his farm in New Marlborough for sale or exchange “for a House in New-York.” Case may have remained at odds with other residents of his town, despite the assertions he made in his first advertisement, and decided that he would be better off starting over somewhere else. If so, it was the damage cause by rumors rather than the danger and destruction of battles that displaced him from his farm during the Revolutionary War.