What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The Papers taken out by evil minded persons, who had no manner of right to them.”

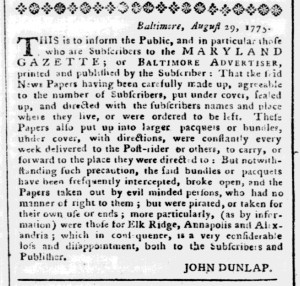

Something went wrong. John Dunlap, the printer of Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, had a system for delivering his newspaper to subscribers who lived outside of Baltimore, but “evil minded persons” interfered with it. In particular, disruptions occurred in Annapolis and Elk Ridge, both in Maryland, and Alexandria, Virginia. That prompted Dunlap to run a notice in the August 29, 1775, edition, placing it immediately after local news and first among the advertisements to increase the likelihood that readers would see it.

The exasperated printer went into great detail about his delivery infrastructure, hoping to convince “the Public, and in particular those who are Subscribers” that he made every effort to follow through on his obligation to deliver the newspaper. The correct number of copies had been “carefully made up, agreeable to the number of Subscribers, put under covers, sealed up, and directed with the subscribers names and place where they live, or were ordered to be left.” Then, those newspapers were “also put up into larger pacquets or bundles, under cover, with directions” and “constantly every week delivered to the Post-rider or other, to carry, or forward to the place they were directed to.” Despite such careful attention and “notwithstanding such precaution, the said bundles or pacquets have been frequently intercepted, broke open, and the Papers taken out by evil minded persons, who had no manner of right to them.” Dunlap called this “a very considerable loss and disappointment, both to the Subscribers and Publisher.” Advertisers may have also been frustrated upon learning that the notices they paid to insert in Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette did not circulate as widely as they expected. The printer likely realized that could have an impact on revenue as well.

Dunlap declared that the missing newspapers “were pirated, or taken for their own use or ends” by the thieves. Despite the consequences for subscribers, advertisers, and the printer, the motivation for taking the newspapers may not have been completely nefarious. In the wake of recent events – the battles at Lexington and Concord, the Battle of Bunker Hill, the Second Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia, colonial assemblies holding their own meetings, George Washington assuming command of the Continental Army as it besieged Boston – colonizers were eager for news. Some may have resorted to unsavory means of getting the latest updates, taking newspapers that did not belong to them. That did not justify what they did, but it does testify to the role of the early American press in disseminating information about the imperial crisis and the Revolutionary War. Some colonizers became better informed because of the theft, while subscribers to Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette had to seek out other newspapers or rely on conversations and correspondence to learn the latest updates.