What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

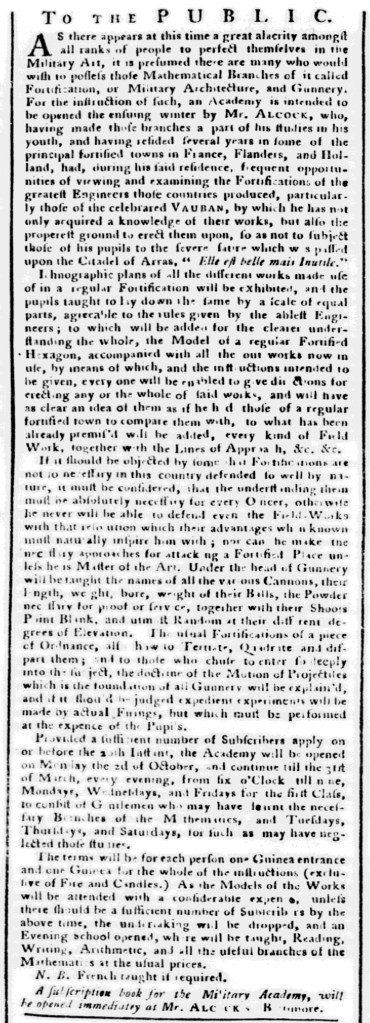

“A subscription book for the Military Academy, will be opened immediately.”

In the fall of 1775, Mr. Alcock advertised an academy with a specialized curriculum. “AS there appears at this time a great alacrity amongst all ranks of people to perfect themselves in the Military Art,” he declared to readers of the Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette and the Maryland Journal, “it is presumed there are so many who would wish to possess those Mathematical Branches of it called Fortification, or Military Architecture, and Gunnery.” To that end, Alcock, announced his plans to open a school to teach those subjects. For his qualifications, he noted that he “made those branches a part of his studies in his youth.” In addition, he “resided several years in some of the principal fortified towns in France, Flanders, and Holland.” While there, he took advantage of “frequent opportunities of viewing and examining the Fortifications of the greatest Engineers those countries produced.” In the first year of the Revolutionary War, Alcock was not the only colonizer to advertise a school of this sort. In the summer of 1775, John Vinal advertised that he taught “the Doctrine of Projectiles, or Art of GUNNERY,” at his school in Newburyport, Massachusetts.

In advance of opening his academy in Baltimore on October 2, Alcock began advertising in early September. His lengthy notice appeared in the Maryland Journal on September 6, 13, and 20. It may have run in Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette as early as September 5, but that issue, if it survives, has not been digitized for wider accessibility. Alcock’s advertisement did appear in that newspaper for at least five weeks from September 12 through October 10. With the last two insertions, he likely hoped to pick up stragglers who had not yet enrolled yet had not missed so many classes to join the academy. From the start, Alcock advised that a “subscription book for the Military Academy, will be opened immediately,” allowing students to commit to enrolling by signing their names. Prospective students could also peruse the list to see who else in their community planned to attend. Alcock intended to divide his pupils into two classes, one cohort consisting of “Gentlemen who may have learnt the necessary Branches of the Mathematics” on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays and another series of classes “for such as may have neglected those studies” on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays.

Yet Alcock would offer the course on fortifications and gunnery only if “a sufficient number of Subscribers” enrolled. Those interested in this enterprise needed to encourage their friends and neighbors to sign up or else risk having the classes canceled. If Alcock did not have enough students, “the undertaking will be dropped and an Evening School opened, where will be taught, Reading, Writing, Arithmetic, and all the useful branches of the Mathematics at the usual prices.” The schoolmaster did not want to resort to that. Accordingly, he attempted to convince prospective students of the necessity of his lessons. “If it should be objected by some that Fortifications are not so necessary in this country defended so well by nature,” he argued, “it must be considered, that the understanding them must be absolutely necessary for every Officer, otherwise he never will be able to defend even the Field-Works with that resolution which their which their advantages when known must naturally inspire him; nor can he make the necessary approaches for attacking a Fortified Place unless he is Master of the Art.” Prospective students apparently did not find that convincing. On November 7, Alcock returned to Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette to advertise an evening school “where will be taught Reading, Writing, and Arithmetic” as well as “French, and the most useful branches of the Mathematics, at the usual prices.” Either he never attracted enough students to open his “Military Academy” or classes fizzled out shortly after they began.