What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

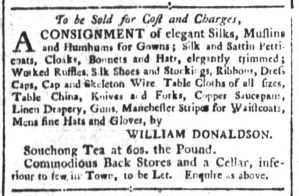

“Souchong Tea at 60s. the Pound.”

As summer approached in 1774, William Donaldson advertised a variety of goods in the South-Carolina and American General Gazette. On May 27, he promoted “elegant Silks, Muslins and Humhums for Gowns; Silk and Sattin Petticoats, Cloaks, Bonnets and Hats, elegantly trimmed; [and] Table China,” among other merchandise. He had a separate entry for “Souchong Tea at 60s. the Pound.” As in other towns, decisions about buying, selling, and consuming tea were part of an unfolding showdown between the colonies and Parliament.

Residents of Charleston were well aware of the Boston Tea Party that occurred the previous December. They also anticipated some sort of response from Parliament, but at the time that Donaldson ran his advertisement, word of the Boston Part Act had not yet arrived in South Carolina. Indeed, four days after Donaldson’s advertisement appeared in the South-Carolina and American General Gazette, another newspaper, the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journalcarried updates from London, dated March 15, that included an overview of the proposed act to close Boston Harbor until the town paid for the tea that had been destroyed and “made proper concession for their tumultuous behaviour.” In addition, the report stated that a “light vessel is said to have been kept ready by some friends to the Bostonians in England, in order to carry accounts of the first determination of a Great Assembly.” By the end of May, colonizers in New England and New York knew that the Boston Port Act had passed and would go into effect on June 1. The news was still making its way to South Carolina.

When it arrived, Peter Timothy, the printer of the South-Carolina Gazette, considered it momentous enough to merit an extraordinary, a supplemental issue. Timothy usually published his newspaper on Mondays, but felt that this news could not wait three more days. He rushed the South-Carolina Gazette Extraordinary to press on Friday, June 3. The masthead included thick black borders, traditionally a sign of mourning the death of an influential member of the community but increasingly deployed by American printers to lament the death of liberty. Confirmation of the Boston Port Act inspired new debates about consuming tea and purchasing other imported goods, eventually leading to a boycott known as the Continental Association, but colonizers did not immediately forego buying, selling, drinking, or advertising tea following the Boston Tea Party. That happened over time (and loyalists like Peter Oliver claimed that even those who claimed to support the boycott devised ways to cheat). In the interim, Donaldson continued marketing tea along with other merchandise.