Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Forty or fifty valuable SLAVES … Also, Sundry Plantations and Tracts of Land.”

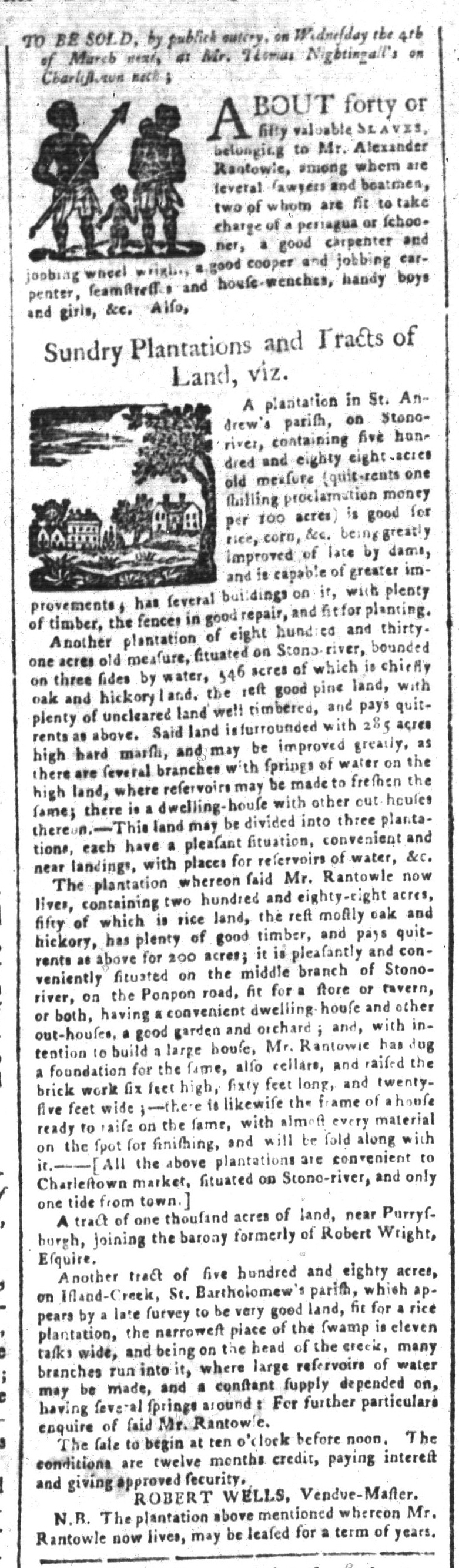

The vast majority of colonial newspaper advertisements did not include visual images. When illustrations did appear with advertisements, they usually came from one of four categories. Images of ships at sea accompanied notices for vessels seeking passengers and freight, though they occasionally appeared in advertisements for imported goods. Depictions of horses ran alongside announcements by breeders offering stallions “to cover” mares. Images of slaves served two purposes: they were included with both advertisements seeking to sell slaves and notices that warned about runaways. (Curiously, similar advertisements for indentured servants were much less likely to include depictions of runaways making their escape.) Finally, real estate advertisements sometimes included images of houses or pastoral scenes. In each case, the woodcut belonged to the printer and could be used interchangeably with advertisements placed for similar purposes. On occasion, some advertisers commissioned their own woodcuts to attract attention to their advertisements, usually opting for an image that replicated their shop signs.

From the standard categories of woodcuts, all four appeared in the February 13, 1767, issue of the South-Carolina and American General Gazette. No advertisers, however, spiced up their notices with original illustrations. That did not mean that the advertising in that issue lacked creativity when it came to the deployment of visual images. When advertisements included woodcuts they tended to have only one. Vendue master Robert Wells, however, oversaw the sale of both “forty or fifty valuable SLAVES” and “Sundry Plantations and Tracts of Land.” He opted to include both types of relevant woodcuts in his notice, a choice that likely resulted in readers noticing the rich visual texture of his advertisement. Given that Wells was charged with selling both slaves and real estate, he may have believed that if he was going to include any sort of woodcut at all then using both images was necessary. After all, readers might have passed over an advertisement showing just a slave or just a plantation, assuming that the woodcut summarized the contents of the entire notice. In a newspaper with few illustrations, Wells’ advertisement with two woodcuts stood out from the rest of the content.