What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

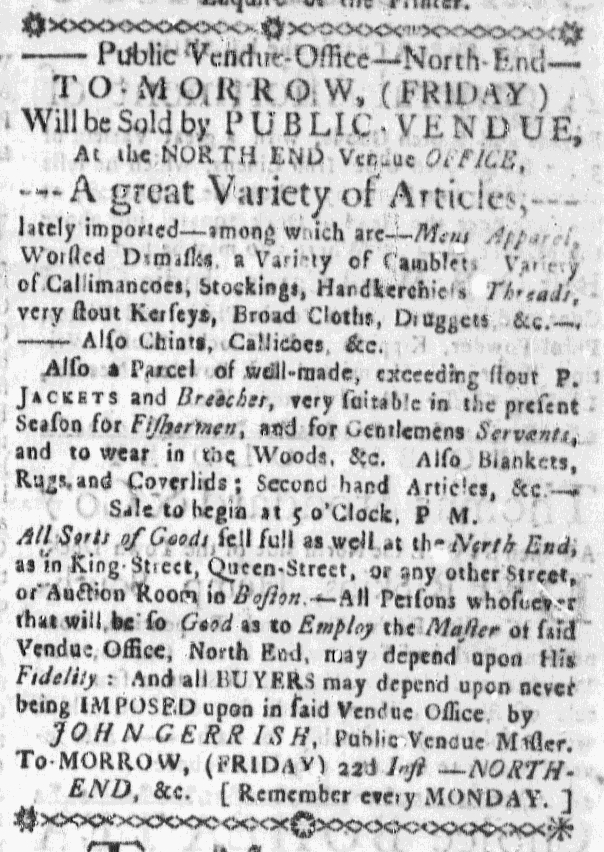

“PUBLIC VENDUE, At the NORTH END Vendue OFFICE.”

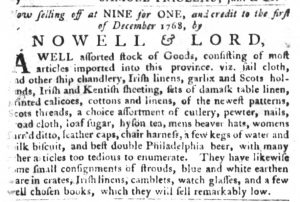

Auctioneer John Gerrish inserted advertisements in the Massachusetts Gazette to encourage residents of Boston and its environs to buy and sell at his “Public Vendue-Office” in the North End. His upcoming auctions included “A great Variety of Articles, — lately imported,” including “Mens Apparel,” a “Variety of Callimancoes,” and “a Parcel of well-made, exceeding stout P. JACKETS and Breeches, very suitable in the present Season for Fishermen.” In addition to new merchandise, he also auctioned “Second hand Articles.” This selection matched the inventories listed in advertisements for shops and other auction houses in local newspapers.

To convince both buyers and sellers to do business at his establishment, Gerrish asserted that the experience would compare favorably to commercial transactions conducted elsewhere in the urban port. “All Sorts of Goods sell full as well at the North End,” he proclaimed, “as in King-Street, Queen-Street, or any other Street, or Auction Room in Boston.” In a bustling city, readers had many choices when it came to venues for buying and selling consumer goods. Gerrish did not want them to dismiss the North End out of hand.

The “Public Vendue Master” also underscored that buyers and sellers could depend on fairness when they made their transactions at the “NORTH END Vendue OFFICE.” Realizing that some readers might indeed have preferences for familiar shops and auction houses elsewhere in the city, he strove to bolster his reputation by assuring potential clients and customers that they had nothing to lose if they instead chose his vendue office. Those who decided to “Employ the Master of said Vendue Office” could “depend upon His Fidelity,” trusting that he made every effort to market their merchandise prior to the auction and encourage the highest possible returns during the bidding. Invoking his “Fidelity” also suggested that he kept accurate books and did not attempt to cheat sellers, especially those who could not be present at an auction to witness the bidding. Yet he also served those looking to make purchases, stressing that “all BUYERS may depend upon never being IMPOSED upon in said Vendue Office.” Gerrish pledged not to unduly pressure prospective customers who attended his auctions. Even as he worked as an intermediary who executed exchanges between buyers and sellers, he wanted each to feel as though they ultimately remained in charge of their commercial transactions rather than relinquishing control to potential manipulation on his part.

John Gerrish, Public Vendue Master, did more than merely announce that he conducted auctions in Boston’s North End. He encouraged both buyers and sellers to participate by instilling confidence in the process, promising that he faithfully served them. Colonists had many choices when it came to acquiring and selling consumer goods. Gerrish used his advertisement to assure them that doing business at his auction house was an option well worth their consideration.