GUEST CURATOR: Charlotte Hatcher

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

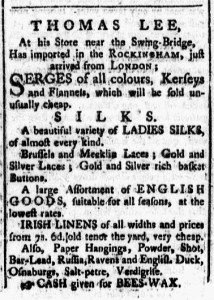

“A large Assortment of ENGLISH GOODS.”

Thomas Lee sold many fabrics and other household goods from his shop “near the Swing-Bridge” in Boston in 1772. This advertisement originally caught my eye due to the “ENGLISH GOODS” he advertised. After the Townshend Acts placed duties on glass, lead, paper, paints and tea in 1767, many colonists used social pressure to boycott goods imported from England. In a broadside issued by the town clerk of Boston in late October 1767, the notes about a town meeting listed items that colonists agreed to boycotted out of protest. Residents of the town of Boston, according to the broadside, were encouraged to “take all prudent and legal Measures to encourage the Produce and Manufactures of this Province, and to lessen the Use of Superfluities” imported from England. The list of boycotted goods included many items that Thomas Lee advertised less than five years later. Colonists quickly resumed buying those goods as soon as Parliament repealed the duties on most of the items in the Townshend Acts and even though Parliament did not repeal the duty on tea.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Not surprisingly, we spend a lot of time examining the consumer revolution of the eighteenth century in my Revolutionary America class. Understanding changing consumption habits provides important context for understanding political participation during the imperial crisis that eventually resulted in thirteen colonies declaring independence. I challenge my students to think about political participation broadly, not just as voting or serving in a colonial legislature. We discuss various ways that everyday activities, including shopping, became political statements. Colonizers could not remain neutral when they made decisions about consumption. They either supported colonial liberties by choosing not to purchase imported goods or they supported Parliament by ignoring the nonimportation agreements adopted by their fellow colonizers. Merely thinking about consumption forced colonizers to think about the political implications as well the repercussions they faced from friends and neighbors for the decisions they made.

That meant that colonizers of various backgrounds participated in politics. Affluent colonizers chose whether to curtail extravagant consumption habits, yet colonizers of more humble means also made decisions about whether to make purchases. Men considered the politics of consumption, as did women who desired the “beautiful variety of LADIES SILKS” that Thomas Lee and other shopkeepers advertised in the 1760s and 1770s.

That political participation, as Charlotte notes, was not a steady crescendo. By the time that Lee placed his advertisement for “ENGLISH GOODS, suitable for all seasons,” colonizers already enacted nonimportation agreements twice and then eagerly resumed consuming imported goods as soon as Parliament met their demands, first in response to the Stamp Act and later in response to the Townshend Acts. Indeed, colonizers were so eager to once again gain access to imported goods and merchants and shopkeepers were so eager to resume business as usual that the nonimportation agreements enacted in response to the Townshend Acts lapsed even though duties on tea remained in place. Some colonizers objected, encouraging their communities to continue the boycotts until they achieved all of their goals, but the pull of commerce and consumption was so strong among the majority of colonizers that the most strident advocates of defending colonial liberties managed to delay the resumption of trade and consumption only briefly. Colonizers adjusted how they interpreted the politics of consumption in the wake of new developments on several occasions.