GUEST CURATOR: Catherine Hurlburt

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

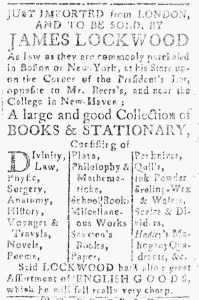

“Penknives, Quills, Ink Powder, Sealing-Wax & Wafers.”

In this advertisement, James Lockwood put up for sale an array of books on various subjects, as well as different writing tools. Lockwood emphasized that these commodities were English, “JUST IMPORTED from LONDON,” which may have been enticing to some colonists. Even though in 1772 the relationship between Britain and the colonies was deteriorating, many colonists still considered themselves to be British, and having English goods was considered a sign of status throughout the colonies, making these goods more desirable.[1]

Today, some readers might find that the writing utensils pique their interest and become curious about writing in the eighteenth century. Colonists mixed their own ink from ink powder and wrote with pens made by sharpening quills with penknives. Lockwood sold all of those items that are so different from the writing tools we use today. Another interesting difference between then and now is the age at which people who learned to write began their lessons. According to Rachel Bartgis, reading education began around age four and lasted until age seven, but writing did not occur until around age nine. This is because writing with a quill took higher fine motor ability than using today’s pen or pencil. In contrast, children learn reading and writing at the same time today. In addition, colonists learned “cursive” because “print,” named after the script on the printing press, was only used for special purposes, such as labelling parcels.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

In the advertisement that Catherine selected to feature today, James Lockwood updated a notice that he first published in the Connecticut Journal more than two months earlier. He began 1772 by placing an advertisement to advise consumers in New Haven and the nearby towns that he “is now opening, at a new Store, … a great Assortment of English & India GOODS, BOOKS, and all kinds of STATIONARY.” He pledged that he sold his merchandise “Wholesale or Retail, at least as cheap as any of his Neighbours.”

As Lockwood settled in at his new store, he decided to emphasize his “large and good Collection of BOOKS & STATIONARY” in his next advertisement, mentioning his “great Assortment of ENGLISH GOODS” only after listing the various kinds of books he had in stock. He did not mention any titles, but instead announced that he carried “Divinity, Law, Physic, Surgery, Anatomy, History, Voyages& Travels, Novels, Poems, Plays, Philosophy & Mathematicks, School Books, Miscellaneous Works, [and] Seaman’s Books.” Each genre received its own line in a portion of the advertisements divided into three columns. That made the list easier for readers to peruse and areas of interest more visible to prospective customers. The unique format also distinguished Lockwood’s advertisement from others on the page. The third column included the various writing implements that Catherine examined.

Lockwood continued to promote his low prices, though he further enhanced that appeal. Rather than claiming that he set process “at least as cheap as any of his Neighbours,” he instead looked to competitors in Boston and New York. Lockwood declared that his customers acquired books, stationery, and “ENGLISH GOODS” from him “As low as they are commonly purchased” in those larger ports. Prospective customers did not need to travel or send away to merchants and shopkeepers in those cities. Instead, they could find the best bargains right in New Haven.

Lockwood’s proximity to “the College in New-Haven” (now Yale University) may have inspired him to publish an updated advertisement that focused on books and stationery. He did not rely on a single newspaper notice to attract customers to his new Store. Instead, he tried different methods of marketing his wares and generating name recognition among readers of the Connecticut Journal.

**********

[1] T.H. Breen, “An Empire of Goods: The Anglicization of Colonial America, 1690-1776,” Journal of British Studies 25, no. 4 (October 1986): 476.