What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He had no Intention of injuring his Country, or of defending any one unfriendly to its Cause.”

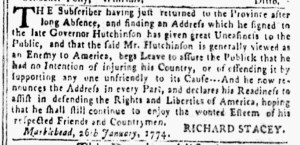

It was yet another public disavowal of an address honoring Thomas Hutchinson, the former governor of Massachusetts, that many colonizers signed when he returned to England. This time, Richard Stacey inserted his recantation in the February 7, 1775, edition of the Essex Gazette. Similar advertisements began appearing in that newspaper and sometimes newspapers printed in Boston as early as July 1774. Stacey explained that he waited several months because he “just returned to the Province after long Absence” and only upon his arrival did he discover “an Address which he signed to the late Governor Hutchinson has given great Uneasiness to the Public.” He further explained that the former governor “is generally viewed as an Enemy to America.”

That being the case, Stacey “begs Leave to assure the Publick that he had no Intention of injuring his Country, or of offending it by supporting any one unfriendly to its Cause.” Accordingly, “he now renounces the Address in every Part, and declares his Readiness to assist in defending the Rights and Liberties of America.” With such a proclamation, disseminated far and wide in the newspaper, Stacey desired “that he shall still continue to enjoy the wonted Esteem of his respected Friends and Countrymen.” He considered the prospects of reconciling with friends, neighbors, and associates worth the expense of placing an advertisement in the Essex Gazette.

Was Stacey sincere? Or did he merely seek to return to the good graces of his community and simply get along during difficult times? That is impossible to determine from his advertisement. It did differ from some that previously appeared in the public prints. For instance, Stacey did not attempt to blame his error on having quickly read the address without considering its implications before signing it. Instead, he did not comment on what had occurred at the time he signed the address but focused on the harm he had done by doing so. Others offered lukewarm assurances that they did not truly support Hutchinson or the policies he had enforced, while Stacey proclaimed his “Readiness to assist in defending the Rights and Liberties of America.” In addition, some signers published advertisements that clearly copied from the same script. Stacey’s was entirely original. That may have been the result of the time that had passed since others inserted their advertisement or the political situation deteriorating and thus requiring stronger assertions from signers of the address branded as Tories. William Huntting Howell suggests that for some readers Stacey’s sincerity may have mattered much less than the fact that he felt compelled to express support for the “Cause” of “his Country” in print.[1]

**********

[1] William Huntting Howell, “Entering the Lists: The Politics of Ephemera in Eastern Massachusetts, 1774,” Early American Studies 9, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 191, 208-215.