What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“The elegant POEM, which the Committee of the Town of Boston had voted unanimously to be Published with the ORATION.”

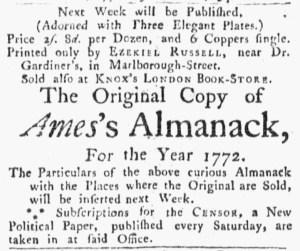

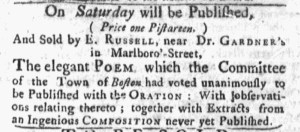

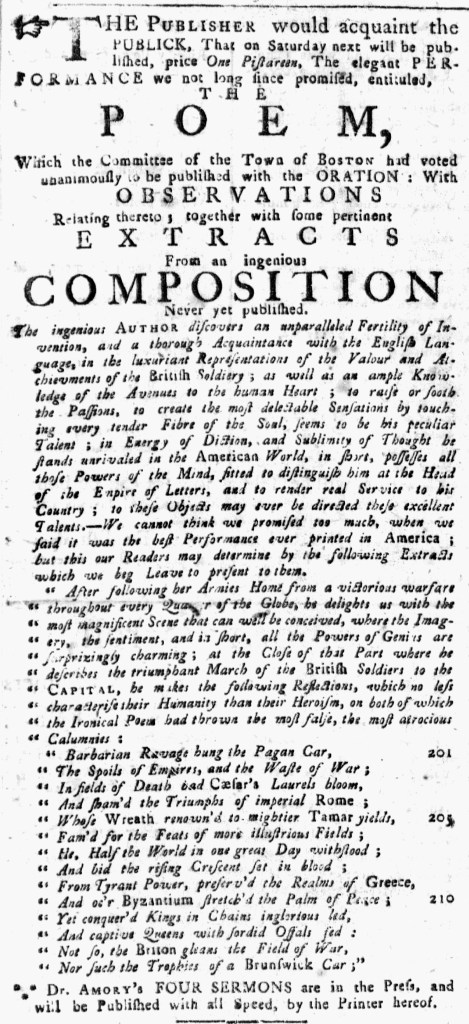

The May 4, 1772, edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy carried a brief advertisement for “The elegant POEM, which the Committee of the Town of Boston had voted unanimously to be Published with the ORATION.” The “ORATION” referred to the address that Dr. Joseph Warren delivered on the second anniversary of the Boston Massacre, an address already published and advertised in several newspapers in Boston and beyond. Why, if “the Committee of the Town of Boston had voted unanimously” to publish it with Warren’s oration, had that not occurred?

The advertisement did not name the author of the poem, but many readers knew that James Allen wrote it. Both the American Antiquarian Society and the Massachusetts Historical Society state that the poem “was suppressed due to doubts about Allen’s patriotism and later was republished by Allen’s friends, with extracts from another of his poems, as ‘The Retrospect.’” That narrative draws on commentary that accompanied the poems as well as Samuel Kettell’sSpecimens of American Poetry (1829) and Evert A. Duyckinck and George L. Duyckinck’s Cyclopaedia of American Literature (1856). More recently, Lewis Leary argues that Allen’s “friends” had motives other than commemorating the Bloody Massacre in King Street or demonstrating Allen’s patriotism in the wake of the committee composed of Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and other prominent patriots reversing course about publishing the poem in the wake of chatter that called into question Allen’s politics.

According to Leary, Allen’s poem about the Boston Massacre and “The Retrospect” must be considered together, especially because “the extracts from ‘The Retrospect’ are unabashedly loyalist, praising Britain’s military force, her selfless defense of her colonies, and benevolent rule over them.” Furthermore, the commentary by Allen’s supposed friends “does indeed clear ‘the authors character as to his politics’ and exhibits his ‘political soundness,’ but that character and that soundness are loyalist, not patriot.”[1]

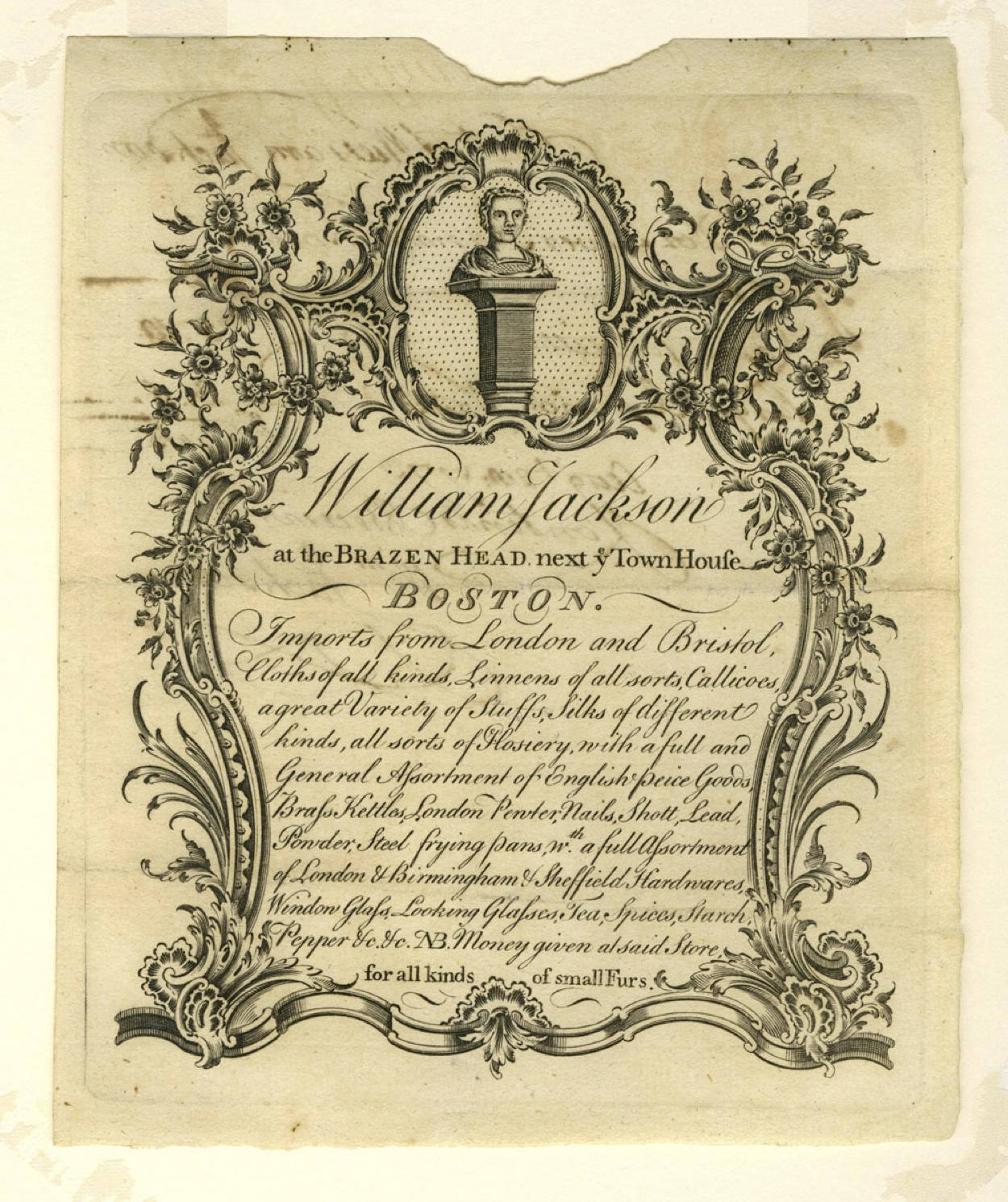

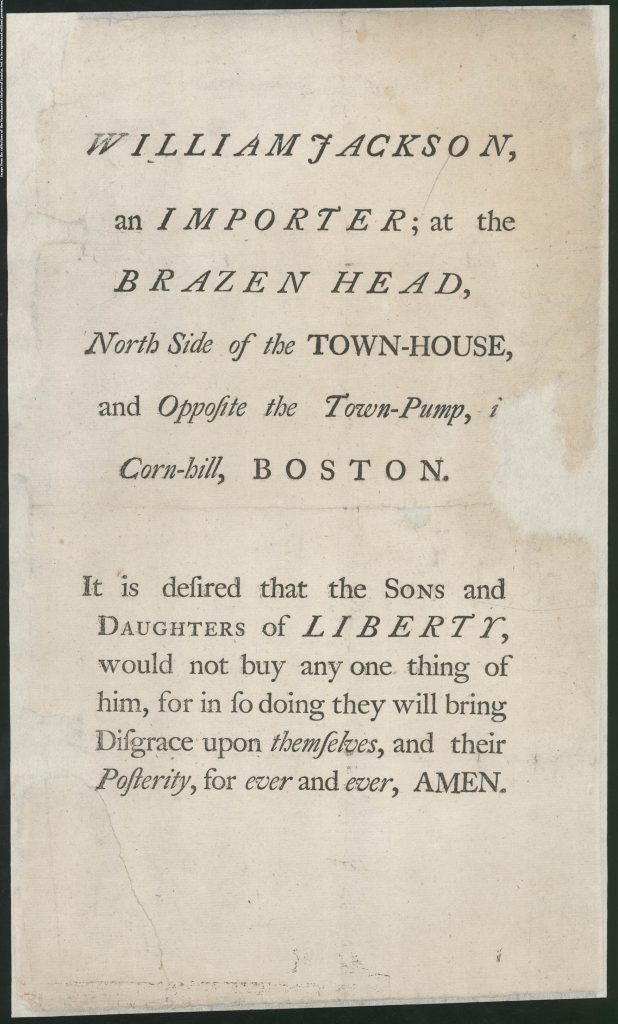

Significantly, Ezekiel Russell published the pamphlet that contained Allen’s poem, “The Retrospect,” and commentary from Allen’s “friends.” He also published the Censor, a weekly political magazine that supported the British government and expressed Tory sympathies. The Postscript that accompanied the final issue of the Censor included a much more extensive advertisement for Allen’s poem, one that included extracts from both the commentary and “The Retrospect.” The portion of the commentary inserted in the advertisement describes how Allen “describes the triumphant March of the British Soldiers to the CAPITAL” and then “makes the following Reflections, which no less characterise their Humanity than their Heroism” in “The Retrospect.” The advertisement praises the “ingeniousAUTHOR” for his “luxuriant Representations of the Valour and Achievement of the British Soldiery.”

Leary argues that Allen’s “friends” sought to discredit Adams, Hancock, and other patriots for being so easily fooled by his poem about the Boston Massacre that seemed to say what they wanted to hear. In that regard, the “publication of his Poem and its antithetical counterpart seems to have been one among many minor skirmishes in the verbal battles between Tories and Patriots on the eve of the Revolution, in which skirmish Allen seems to have been more pawn than participant.” To that end, the “purpose of his ‘friends’ seems clearly to have been to discomfit the committee for its vacillation on the publication of the poem and to expose patriot leaders in Boston as men who could be duped by a skillful manipulator of words.” Allen’s “friends,” according to Leary, did seek to clarify his politics, but with the intention of “certify[ing] him, certainly to his embarrassment, a Loyalist clever enough to mislead his patriot townspeople.”[2]

Still, that may not tell the entire story. Leary argues that “what evidence is available suggests that James Allen as a younger man, like many colonials, had been enthusiastically a loyal British subject, grateful for Britain’s protection of her colonies, but that after the horror of the massacre in Boston on March 5, 1770, had become at thirty-six a patriot who could bitterly challenge the British.”[3] In 1785, Allen’s poem about the Boston Massacre appeared in a collection of orations that commemorated the event, including Warren’s address. By then, the editors who compiled the anthology recognized that Allen wrote the poem “when his feelings, like those of every other free-born American were alive at the inhuman murders of their countrymen.”[4] The controversy had passed, Allen’s poem no longer questioned as an insincere lamentation belied by his earlier work.

**********

[1] Lewis Leary, “The ‘Friends’ of James Allen, or, How Partial Truth Is No Truth at All,” Early American Literature 15, no. 2 (Fall 1980): 166-167.

[2] Leary, “‘Friends’ of James Allen,” 168-169.

[3] Leary, “‘Friends’ of James Allen,” 168.

[4] Quoted in Leary, “‘Friends’ of James Allen,” 170.