What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Pamphlets published on both sides, in the unhappy dispute with Great-Britain.”

As the imperial crisis intensified in the winter of 1775, James Rivington continued to print a newspaper “at his OPEN and UNINFLUENCED PRESS” in New York. He also ran a bookstore, peddling “Pamphlets published on both sides, in the unhappy dispute with Great-Britain.” Both Patriot and Tory printers professed to operate free presses that delivered news and editorials from various perspectives, yet the public associated most newspapers with supporting one side over the other and even actively advocating for their cause. Tory printers invoked freedom of the press as a means of justifying their participation in public discourse rather than allowing Patriot printers to have the only say. When it came to advertising books and pamphlets about current events, Tory printers, especially Rivington, took the more balanced approach.

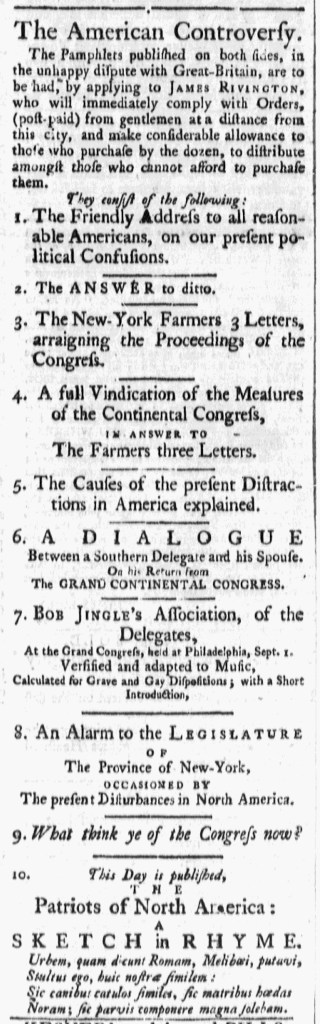

For Rivington, it was a matter of generating revenue as much as political principle. He saw money to be made from printing and selling pamphlets about “The American Controversy.” That was the headline he used for an advertisement that listed ten pamphlets in the February 9, 1775, edition of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer. He previously ran a similar advertisement for “POLITICAL PAMPHLETS … on the Whig and Tory Side of the Question” and another about “The American Contest” that included some of the same pamphlets as well as others. In his “American Controversy” advertisement, Rivington once again offered some familiar titles and new ones. He made clear that the first two represented different positions, “The Friendly Address to all reasonable Americans, on our present political Confusions” and “The ANSWER to ditto,” though he did not indicate which took which side.

The printer positioned this venture as a service that kept the public better informed of the arguments “on both sides.” He sought to disseminate his pamphlets beyond New York to “gentlemen at a distance from this city,” promising to “immediately comply with Orders.” In turn, customers could do their part in making the pamphlets available far and wide since Rivington made “considerable allowance” or deep discounts “to those who purchase by the dozen, to distribute amongst those who cannot afford to purchase them.” Though he portrayed himself as a fair dealer who marketed pamphlets “on both sides,” he did not express any expectation that customers would purchase or distribute both Patriot and Tory pamphlets. Rivington presented readers with the freedom to consume (and further disseminate) the ideas they wished, seemingly hoping the public would allow him the same freedom in printing the content that he wished. Whether he was sincere in such idealism or sought to justify printing editorials and pamphlets that many found objectionable, Rivington increasingly ran afoul of Patriots who did not share his outlook on freedom of the press when it came to disseminating news and opinion that favored the Tory side in “the unhappy dispute with Great-Britain.”

[…] he followed the lead of James Rivington in New York and tried to profit from selling pamphlets “on both sides, in the unhappy dispute with Great-Britain.” As the imperial crisis reached its boiling point in April 1775, Aikman took to the pages of […]

[…] and pamphlets with a common theme. With a headline proclaiming, “The American Controversy,” an advertisement published in February 1775 listed ten pamphlets “published on both sides, in the unhappy dispute with Great-Britain.” He […]