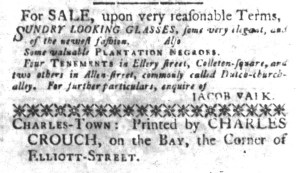

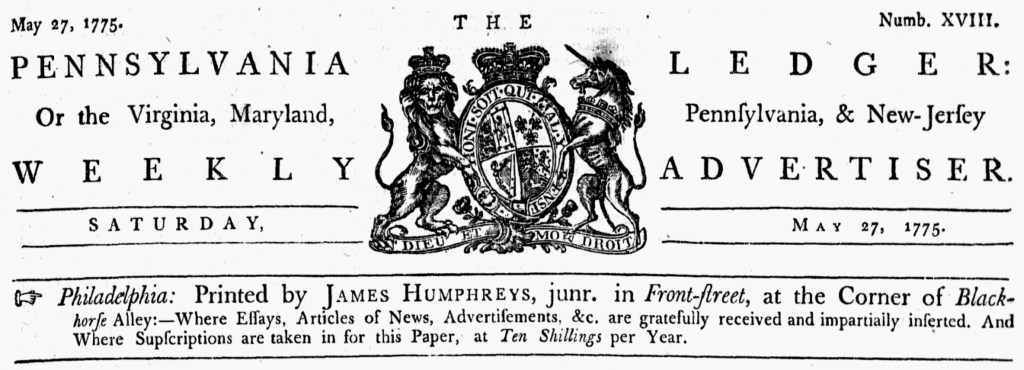

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The Publisher of this paper will be supplied with the most early and authentic Intelligence from all parts of the continent.”

Four weeks after commencing publication of the Massachusetts Spy in Worcester at the beginning of May 1775, Isaiah Thomas continued building the infrastructure necessary to operate a successful newspaper. The Massachusetts Spy had been published in Boston since July 1770, but Thomas removed his press from the city and sent it to Worcester shortly before the battles at Lexington and Concord. He had previously intended to install a junior partner in a printing office in Worcester and oversee publication of a new newspaper from afar, but he became increasingly nervous about remaining in Boston since his ardent advocacy for the patriot cause drew the attention of British officials and Loyalist colonizers. Fearing for his safety, he revised his plans, removing the Massachusetts Spy to Worcester and giving it a new secondary title, American Oracle of Liberty.

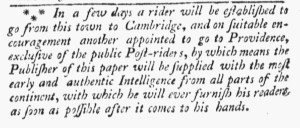

In the May 31 edition, Thomas continued to run subscription proposals that gave information about the newspaper, including its size (“large folio”), day of publication (“every WEDNESDAY Morning, as early as possible), and price (“Six Shillings and Eight Pence per annum”). He also solicited advertisements and listed about two dozen local agents who accepted subscriptions in various towns in Worcester County. In addition to the subscription proposals, Thomas inserted a new notice that announced, “In a few days a rider will be established to go from this town to Cambridge,” where the Massachusetts Provincial Congress met during the siege of Boston, “and on suitable encouragement another appointed to go to Providence, exclusive of the public Post-riders.” Why did Thomas hire his own riders? He explained that “the publisher of this paper will be supplied with the most early and authentic Intelligence from all parts of the continent,” the latest news “which he will ever furnish his readers, as soon as possible after it comes to his hands.” Although Worcester is the second largest city in New England today, it was a small town in 1775. It was not a hub for collecting information about current events, but Thomas aimed to change that. He devised a plan for getting letters from Cambridge and newspaper from throughout the colonies via Providence. Moving the Massachusetts Spy to Worcester meant establishing new means of gathering the news to collate into the newspaper to keep readers well informed. Thomas was so committed to that endeavor that he employed his own riders rather than depending solely on those who already had routes that connected Worcester to Cambridge or Providence.