What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

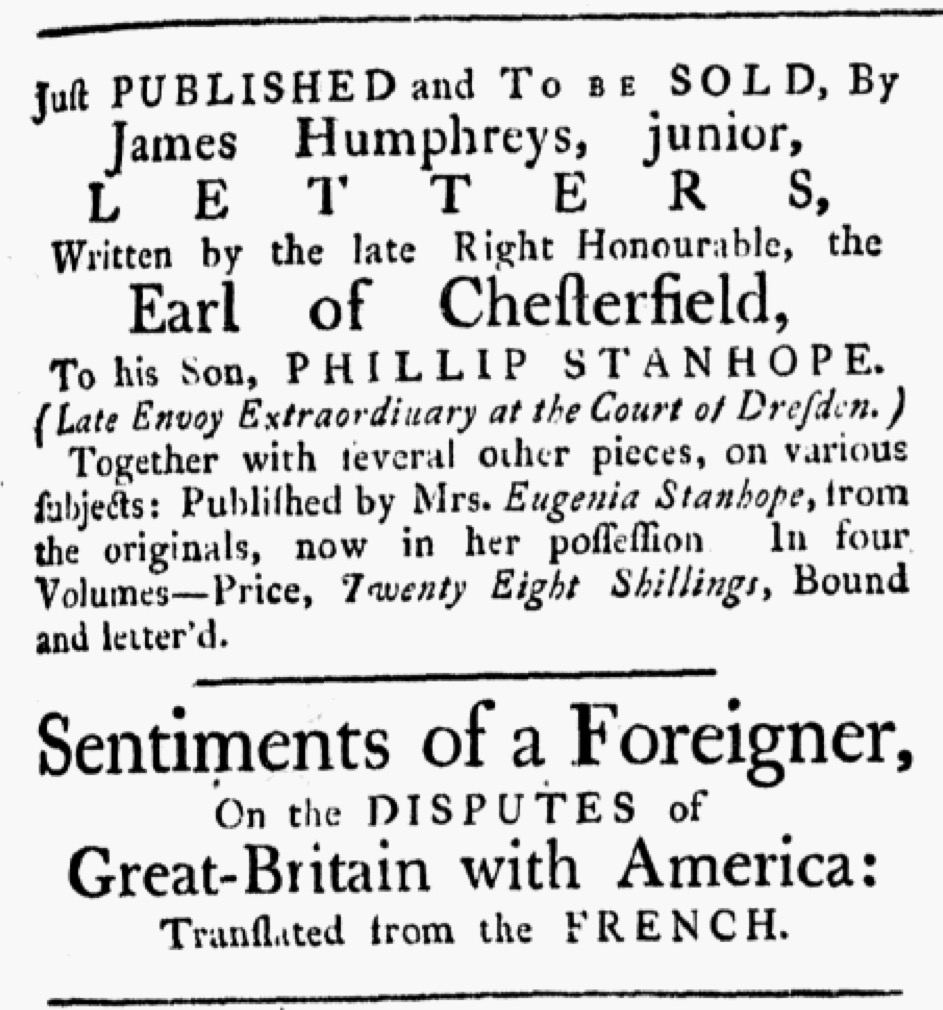

“LETTERS, Written by the late Right Honourable, the Earl of Chesterfield, To his Son.”

James Humphreys, Jr., led the September 2, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger with an advertisement for Letters by the Late Right Honourable, the Earl of Chesterfield, to His Son, Phillip Stanhope. Although the header proclaimed, “Just PUBLISHED and TO BE SOLD, By James Humphreys, junior,” the printer of the Pennsylvania Ledger merely sold copies of a book printed by others. As was often the case, the phrase “Just PUBLISHED” meant that a book, pamphlet, print, or other items was now available for purchase, but advertisers expected readers to separate “Just PUBLISHED” and “TO BE SOLD.” Only the latter applied to the advertiser. In this case, Humphreys likely stocked copies of an American edition printed by Hugh Gaine and James Rivington in New York.

Prospective customers did not care nearly as much about who printed the book as they did about the contents. The advertisement (drawn from the extended title of the work) indicated that it consisted of four volumes that contained the Earl of Chesterfield’s letters “Together with several other pieces, on various subjects: Published by Mrs. Eugenia Stanhope, from the original, now in her possession.” The earl had written 448 letters to his son between 1737, when the boy was five, and his death in 1768. At that time, the early learned that his son had been secretly wed for a decade and had two sons of his own. The earl provided for his grandsons but did not support their mother. In turn, she published the collection of letters.

The letters caused a stir in both Britain and America. They presented a guide to manners for gentlemen to navigate aristocratic society, prompting colonizers concerned with demonstrating their own gentility to take note of the advice the earl offered to his son. Yet readers did not universally celebrate the attitude and conduct the early advocated. Some critiqued what they considered cynical and amoral values contained within the letters. While Gaine and Rivington may have found eager audiences for the letters in New York and Humphreys in Philadelphia, readers from New England, the descendants of Puritans, were much more skeptical. Gwen Fries notes that John Adams refused to send Abigail a copy in 1776, advising her that the letters were “stained with libertine Morals and base Principles.” When she did read them a few years later, she agreed that they contained “the most immoral, pernicious and Libertine principals.” In confining his advertising copy to the extended title of the work, Humphreys did not take a position. He likely suspected that even those who had heard that the letters included some unsavory advice would be curious to assess what Chesterfield wrote for themselves. Many others in Philadelphia, the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the colonies, may not have cared much at all about the sorts of objections raised by readers in Boston.

[…] James Humphreys, Jr., led the September 2, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger with an advertisement for Letters by the Late Right Honourable, the Earl of Chesterfield, to His Son, Phillip Stanhope. Although the header proclaimed, “Just PUBLISHED and TO BE SOLD, By James Humphreys, junior,” the printer of the Pennsylvania Ledger merely sold copies of a book printed by others. As was often the case, the phrase “Just PUBLISHED” meant that a book, pamphlet, print, or other items was now available for purchase, but advertisers expected readers to separate “Just PUBLISHED” and “TO BE SOLD.” Only the latter applied to the advertiser. In this case, Humphreys likely stocked copies of an American edition printed by Hugh Gaine and James Rivington in New York. Prospective customers did not care nearly as much about who printed the book as they did about the contents. The advertisement (drawn from the extended title of the work) indicated that it consisted of four volumes that contained the Earl of Chesterfield’s letters “Together with several other pieces, on various subjects: Published by Mrs. Eugenia Stanhope, from the original, now in her possession.” The earl had written 448 letters to his son between 1737, when the boy was five, and his death in 1768. At that time, the early learned that his son had been secretly wed for a decade and had two sons of his own. The earl provided for his grandsons but did not support their mother. In turn, she published the collection of letters. Read more… […]