What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

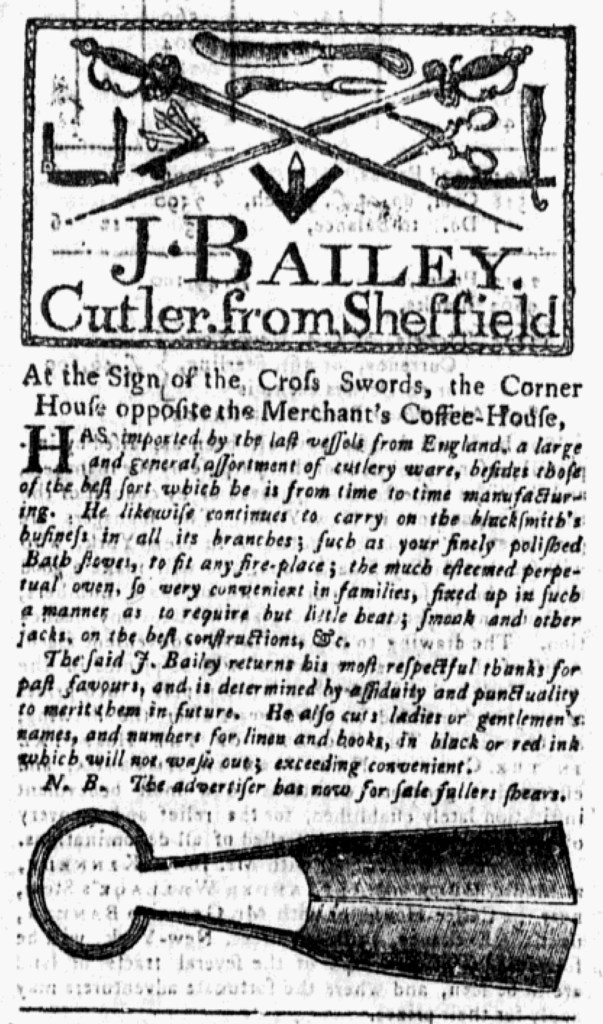

“J. BAILEY. Cutler. from Sheffield.”

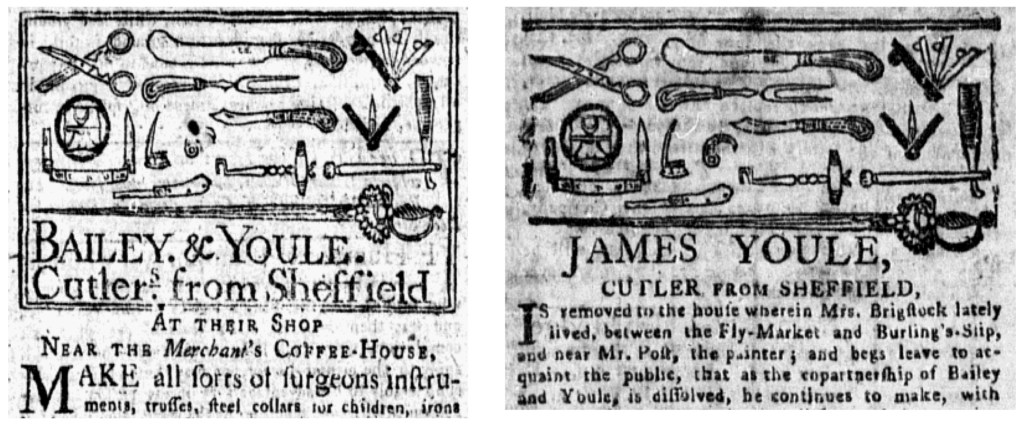

In the early 1770s, cutlers in New York competed with each other not only for customers but also in producing elaborate images to accompany their advertisements in the city’s newspapers. It began in the spring of 1771 with Bailey and Youle, “Cutlers for Sheffield,” running an advertisement with a woodcut depicting more than a dozen items made and sold at their shop, enhancing their list of “surgeons instruments, … knives, razors, shears, and scissors.” Not long after, Richard Sause followed their lead with an advertisement featuring a woodcut depicting more than a dozen items available at his shop. Two items, a knife and a sword, had his name on them, suggesting that he marked his wares so consumers would recall who produced them and, if satisfied with the quality and durability, buy from him again. In that regard, Sause improved on the image distributed by Bailey and Youle, although his competitors may have also marked their cutlery even if the woodcut in the newspaper did not indicate that was the case.

When Bailey and Youle dissolved their partnership a year later, Youle retained the woodcut and modified it to remove any reference to his former associate. Not long after Youle disseminated that image in the public prints, Lucas and Shephard, WHITESMITHS and CUTLERS, From BIRMINGHAM and SHEFFIELD,” published their own advertisement with a woodcut showcasing many of the items they made and sold. Bailey apparently considered that strategy effective for attracting customers (or at least not losing them to his competitors) because he devised his own woodcut that enclosed “J. BAILEY. Cutler. from Sheffield” and several cutlery items within a decorative border. The copy of his advertisement gave his location as “the Sign of the Cross Swords, the Corner House opposite the Merchant’s Coffee-House.” A pair of crossed swords appeared at the center of the woodcut. A second woodcut appeared at the end of the advertisement, under a nota bene that advised that Bailey “has now for sale fullers shears.” The cutler used the additional image to distinguish his notice from those of his competitors. All three advertisements ran in the July 27, 1772, edition of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury (Bailey’s on the third page, Youle’s on the first page of the supplement, and Lucas and Shephard’s on the second page of the supplement). Given the prevalence of images in advertisements placed by his competitors, Bailey may have considered it imperative to get his own woodcut depicting his wares into circulation among consumers in New York.