What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He now employs an excellent Workman from London.”

Charles Stevens, a goldsmith and jeweler, occasionally advertised in the Providence Gazette in the late 1760s and early 1770s. A new development in his workshop prompted each of his advertisements. On September 24, 1768, for instance, Stevens advised the public, “particularly those who have hitherto kindly favoured him with their Custom,” that he moved to a new location “in the main Street of Providence, where he continues to carry on his Business, in all its various Branches, and engages to execute his Work in the best and most elegant Manner.” The goldsmith and jeweler made the same appeals as other artisans, yet they appeared in the public prints only when Stevens wanted to make sure that former clients knew about his new location. Similarly, when he “removed to BROAD-STREET” in the summer of 1771, Stevens placed an advertisement to inform the public, “particularly his old Customers,” that he “carries on his Business in all its Branches, as usual.”

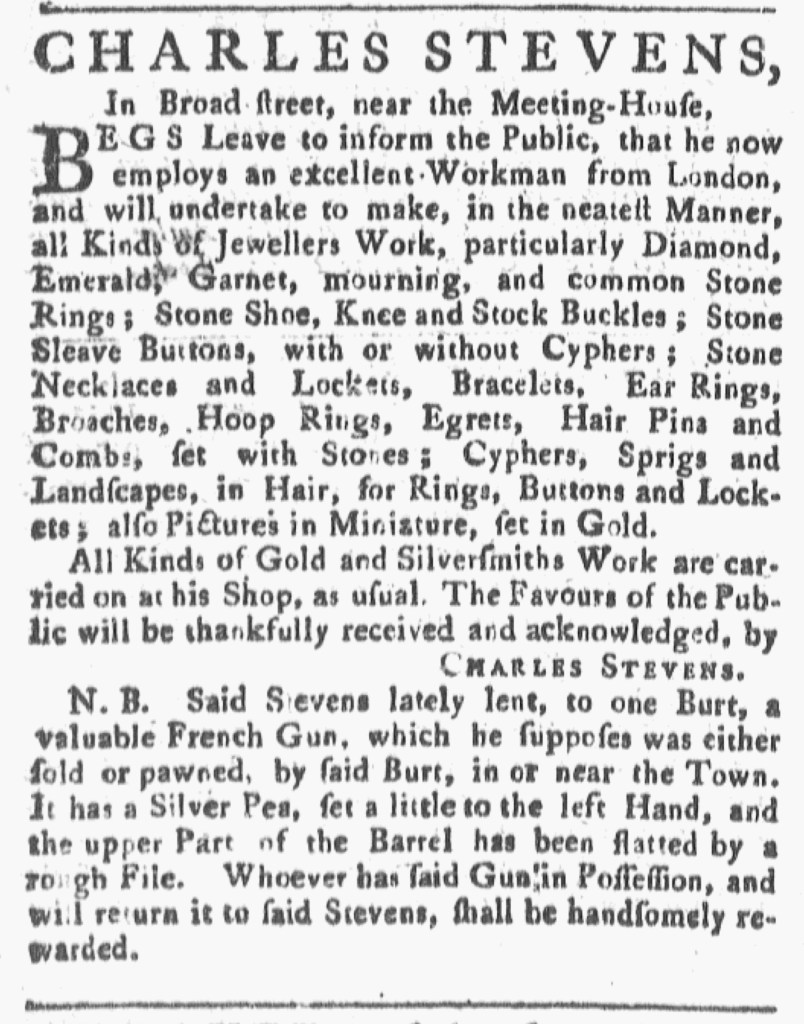

The goldsmith and jeweler had other news to share two years later. In July 1773, he placed an advertisement to announce that “he now employs an excellent Workman from London, and will undertake to make, in the neatest Manner, all Kinds of Jewellers Work.” Artisans who placed newspaper advertisements rarely gave credit to employees and relations who labored in their workshops. Those who did so usually emphasized one or more of three specific reasons. Sometimes an employee or associate possessed expertise that the proprietor did not, expanding the offerings available at the shop. Sometimes their connections to London or other cities suggested greater familiarity with current fashions and tastes as well as superior training in their craft. Sometimes an additional employee testified to the popularity of a workshop, suggesting that the artisan who ran it required assistance to keep up with orders. All three reasons may have applied to the “excellent Workman from London” who produced “all Kinds of Jewellers Work” in Stevens’s shop. The proprietor noted, “All Kinds of Gold and Silversmith’s Work are carried on at his Shop, as usual.” Stevens may have shifted his focus to that work, leaving jewelry orders to his new employee. He had already established his reputation in Providence, accepting jobs “as usual,” yet the addition of an employee with specialized skills merited an advertisement to keep existing customers and the public aware of new developments that benefited his patrons.