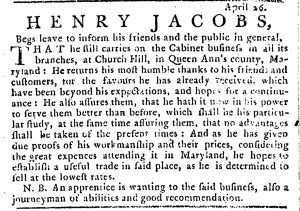

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He still carries on the Cabinet business … no advantages shall be taken of the present times.”

Henry Jacobs had confidence in the circulation of the Pennsylvania Journal when he placed an advertisement in the spring of 1775. Addressing “his friends and the public in general,” he declared that he “still carries on the Cabinet business in all its branches, at Church Hill, in Queen Ann’s county, Maryland.” That small town on the colony’s eastern shore was approximately eighty miles from Philadelphia, the bustling port where William Bradford and Thomas Bradford printed the Pennsylvania Journal, yet Jacobs considered advertising in that newspaper a sound investment. He may not have expected to gain any customers in Philadelphia, but he realized that the Pennsylvania Journal served an extensive readership in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. That meant that “the public in general” in Queen Anne’s County might see his advertisement as copies of the Pennsylvania Journal circulated there.

Yet some of the language in his advertisement suggests that Jacobs did not yet have friends and customers in Maryland. Near the end of his notice, he stated that he “hopes to establish a useful trade in said place,” indicating that he may have been a newcomer there. Perhaps Jacobs relocated from Philadelphia. When he announced that he “still carries on the Cabinet business … at Church Hill,” the “still” may have referred to pursuing his trade but not the location. Jacobs’s advertisement might have been a moving notice, alerting customers that he left one town and opened a workshop in another. He hoped to maintain at least some of his former clientele. If that was the case, it also helps to explain why he chose to advertise in a newspaper published in Philadelphia rather than the Maryland Gazette printed in Annapolis. Furthermore, he sought an apprentice and a journeyman “of abilities and good recommendation,” possibly seeking staff to assist him at his workshop in a new town.

Like many other colonizers who advertised goods and services, Jacobs expressed gratitude to “his friends and customers, for the favours he has already received.” Doing so signaled to readers not familiar with him or his furniture that he was an established artisan. He underscored his skill and experience when he trumpeted that he “has given due proofs of his workmanship.” Jacobs intended to bolster his reputation, especially when he stated that customers previously placed orders “beyond his expectations.” Such appeals could have resonated with customers in both Philadelphia and Queen Anne’s County. The primary purpose of his advertisement, after all, was not to proclaim “his most humble thanks” but instead to drum up new business. To that end, he asserted that he “hath it now in his power to serve [his customers] better than before,” though he did not explain what he meant when he gave those assurances. If he had been in Church Hill for some time, perhaps he made improvements to his workshop or acquired new tools. If he was new to town, he may have referred to his new workshop. Whatever the case, he promised that “no advantages shall be taken of the present times.” Jacobs likely had not heard about events at Lexington and Concord on April 19 when he composed his advertisement and submitted it to the printing office. The “present times” became more complicated as the imperial crisis became a war.