What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Being resolved to decline his Retail Trade … he will sell his Stock of Goods on Hand at the very lowest Rates.”

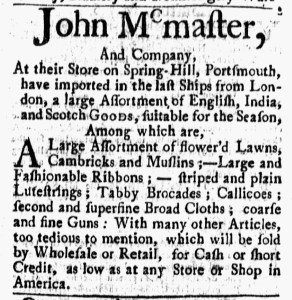

George Bartram had been in business “At the Sign of the GOLDEN FLEECE’s HEAD” in Philadelphia for several years by the time he placed an advertisement in the March 21, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post. He sometimes called his establishment the Woollen-Drapery and Hosiery WAREHOUSE and used visual elements to enhance his advertisements. For instance, a decorative border enclosed the name of his business in some advertisements while others featured a woodcut that depicted that golden fleece’s head. Earlier in his career, he kept shop “at the Sign of the Naked Boy.” An even more elaborate woodcut replicated that sign with a naked boy holding a yard of cloth in a cartouche in the center, flanked by rolls of fabric on either side and the proprietor’s name below them. Bartram was still using the golden fleece’s head woodcut to adorn his advertisements in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet in March 1775, but he did not have a second one to use in the Pennsylvania Evening Post.

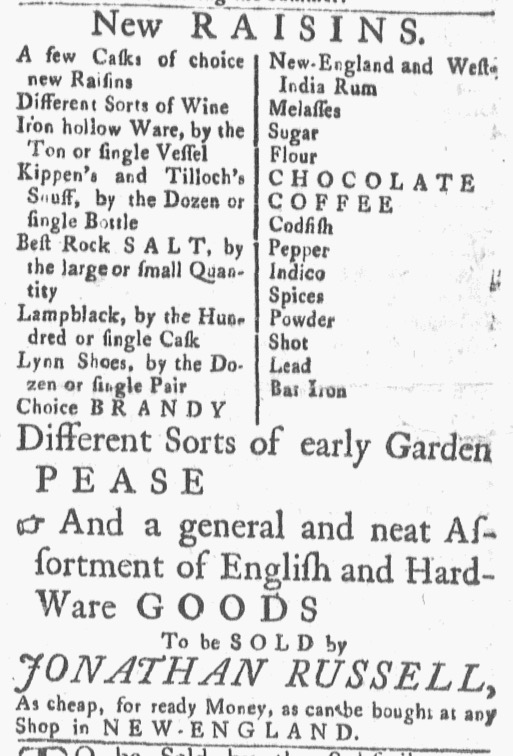

Instead, he relied on advertising copy in making his pitch to prospective customers. As he had often done in previous newspaper notices, Bartram emphasized the array of choices he made available to consumers, promoting a “large and fresh Assortment of MERCHANDIZE.” To demonstrate that was the case, he inserted a lengthy list of goods, such as “Broadcloaths, of the neatest and most fashionable Colours, with suitable Trimmings,” “beautiful buff and white Hair Shags,” “rich black Paduasoys and Satins,” and “handsome Silk and Worsted Stuff for Womens Gowns.” His intended for those evocative descriptions to entice readers. He played to both taste and imagination by making choice a theme throughout his catalog of merchandise: “Handkerchiefs of all Sorts,” “a Variety of Cambricks suitable for Gentlemen’s Ruffles and Stocks,” “a large Assortment of brown and white Russia Sheetings and Hessians,” “an elegant Assortment of the best Moreens,” “a Quantity of the best Rugs,” and “a large Assortment of Hosiery.”

In a final nota bene, Bartram announced that customers could acquire his wares at bargain prices because he was going out of business. He “resolved to decline his Retail trade” and “assures his Friends and the Public that he will sell his Stock of Goods on Hand at the very lowest Rates.” He also offered a discount “to those who purchase a Quantity,” hoping that would offer additional encouragement for prospective customers. Bartram did not indicate why he was closing his business, though the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement adopted throughout the colonies, may have presented an opportunity to liquidate his merchandise and get rid of items that had lingered on the shelves in his Woollen Drapery and Hosiery Warehouse. Bartram was “SELLING OFF” his inventory, offering good deals on absolutely everything.