What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

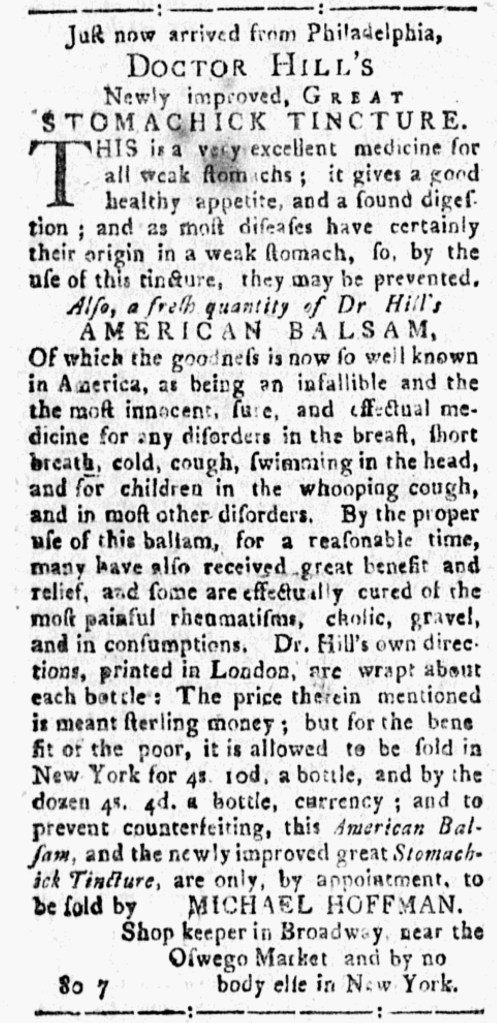

“To be sold by MICHAEL HOFFMAN … and by no body else in New-York.”

In the spring of 1775, Michael Hoffman took to the pages of the New-York Journal to advertise two patent medicines, “DOCTOR HILL’S Newly improved, GREAT STOMACHICK TINCTURE” and “Cr. Hill’s AMERICAN BALSAM.” Even though he asserted that the goodness of that second remedy “is now so well known in America, as being an infallible … end effectual medicine” for a variety of “disorders,” Hoffman listed symptoms that it alleviated. He also advised that the tincture prevented “most diseases” since they tended to have “their origin in a weak stomach.”

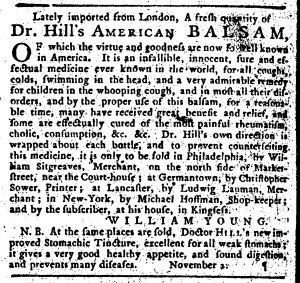

Hoffman declared that his supply had “Just now arrived from Philadelphia.” He likely received it from William Young, an associate who advertised both the tincture and the balsam in the Pennsylvania Journal in November 1774 and in the first issue of Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury in April 1775. Those advertisements included a short list of five local agents who sold Dr. Hill’s medicines in Philadelphia, Germantown, Kingsessing, Lancaster, and New York. The shopkeeper did not incorporate that list into his notice, but he did underscore that “to prevent counterfeiting” the remedies were sold “only, by appointment … by MICHAEL HOFFMAN … and by no body else in New-York.” Judging by an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Packet in May 1772, he held that exclusive “appointment” for at least three years. As another means of guaranteeing authenticity, “Dr. Hill’s own directions, printed in London, are wrapt about each bottle.”

In addition to the patent medicines, Hoffman apparently received copy for his advertisement from Young. Much of it repeated the notices that ran in Philadelphia’s newspapers word for word. In the initial advertisement in November, Young stated that the medicines had been “Lately imported from London.” Hoffman updated that to “Just now arrived from Philadelphia,” not mentioning when his associate there imported them even though he could have affirmed that Young had received the shipment before the Continental Association went into effect on December 1, 1774. Perhaps he depended on his own reputation as sufficient testimony that he did not sell goods in violation of the nonimportation agreement.