What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Mrs. TAYLOR’s BOARDING SCHOOL … [for] young LADIES.”

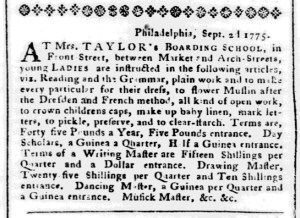

The first advertisement in the September 12, 1775, edition of Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette, published in Baltimore, promoted “Mrs. TAYLOR’s BOARDING SCHOOL” for “young LADIES” on Philadelphia, apparently an elite institution based on the tuition. The headmistress charged forty-five pounds per year along with an initial entrance fee of five pounds. Taylor advised the parents and guardians of prospective pupils that they would be taught “Reading and the Grammar, plain work and to make every particular for their dress, to flower Muslin after the Dresden and French method, all kind of open work, to crown childrens caps, make up baby linen, mark letters, to pickle, preserve, and to clear-starch.” The standard curriculum combined practical skills that prepared young women to run a household with some leisure activities that testified to their status.

Yet that was not the extent of the instruction that took place at Taylor’s boarding school. For additional fees, her charges could opt for additional lessons taught by tutors that Taylor hired. Students learned to form their letters from a “Writing Master” for fifteen shillings each quarter. They learned their steps from a “Dancing Master” for a guinea (or twenty-one shillings) each quarter. Although Taylor did not say so, those students presumably learned to dance with grace rather than focusing exclusively on the mechanics of minuets and other popular dances. Lessons from a “Drawing Master” cost twenty-five shillings per quarter. Taylor also listed a “Musick Mater &c. &c.” but did not note their rates. Repeating the common abbreviation for et cetera twice suggested that other tutors taught painting, French, and other genteel pursuits in addition to singing and playing instruments. Taylor operated her boarding school in the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the colonies. For pupils aspiring to gentility, she could arrange for access to all sorts of instructors, allowing her students and their families to choose which kinds of lessons they needed or desired in addition to the standard curriculum. For the gentry in Baltimore, a port growing in size and importance on the eve of the American Revolution, Taylor’s boarding school for young ladies may have looked very attractive indeed.