What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He pays cash for all kinds of homespun cloths.”

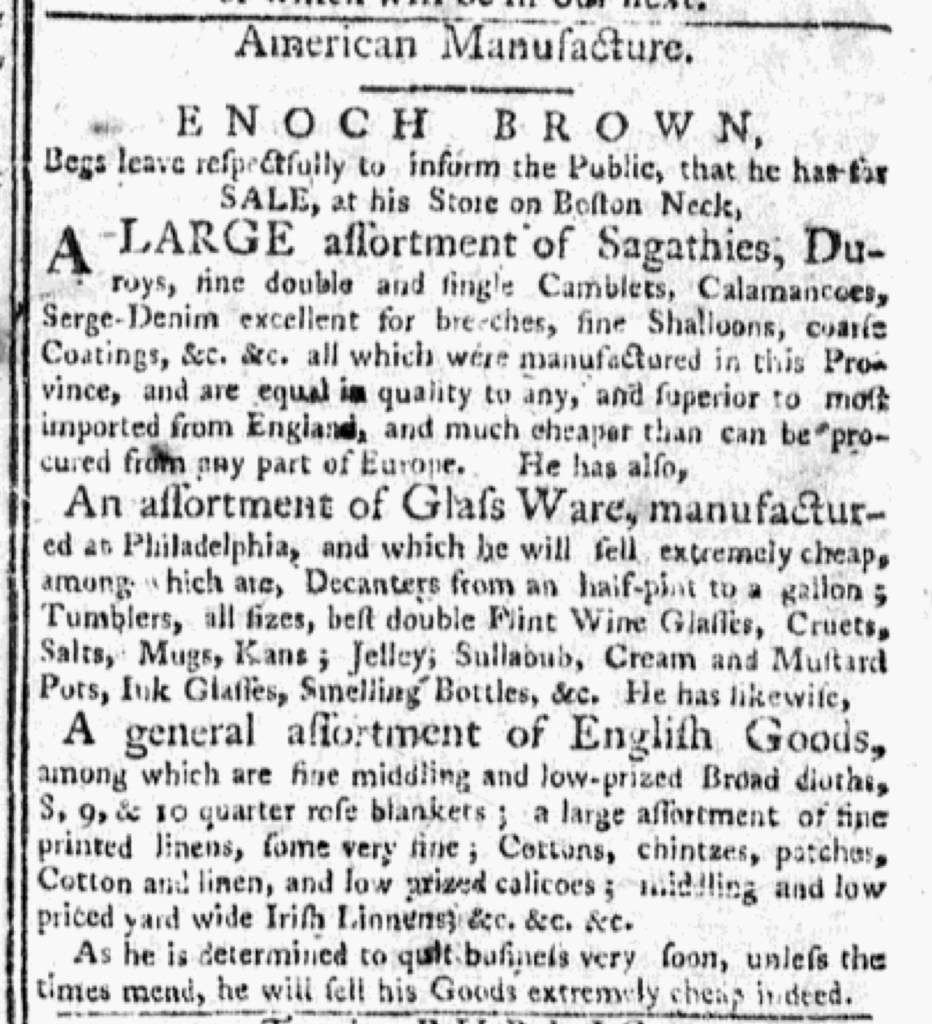

Enoch Brown, a shopkeeper, had a history of promoting domestic manufactures (or goods made in the colonies) as alternative to items imported from Britain. In the spring of 1768, for instance, he ran an advertisement alerting “those Persons who are desirous of Promoting our Own Manufactures … That he takes in all Sorts of Country-made Cloths at his Store on Boston Neck.” In the wake of learning about duties levied on certain imported goods in the Townshend Revenue Act, many colonizers set about organizing nonimportation agreements. They simultaneously embraced goods produced locally as a means of supporting the colonial economy and correcting a trade imbalance with Britain. Several years later, Brown ran another advertisement with similar themes in January 1775. Bearing the headline “American Manufacture,” that notice emphasized that the variety of textiles Brown stocked “were manufactured in this Province, and are equal in quality to any, and superior to most imported from England, and much cheaper than can be produced from any part of Europe.”

Although Brown had been at the same location for years, he departed Boston for Watertown following the battles at Lexington and Concord. That presented challenges for both Brown and his customers, so “for greater Conveniency” he once again moved, this time to “Little-Cambridge” in the fall of 1775. When he opened his shop, he advertised a “Variety of Winter Goods” for the coming season as well as “sagathees, duroys, camblets,” and other textiles “of American manufacture, which he sells extreme cheap.” Customers could acquire any of those for low prices, despite the disruptions taking place as the siege of Boston continued. Committed to giving consumers choices that matched their political principles, Brown sought new merchandise made locally. In a nota bene at the end of his advertisement, he declared that he “pays cash for all kinds of homespun cloths.” In so doing, he filled the role of intermediary between producers and consumers, giving both the opportunity to support the American cause. After all, the Continental Association devised by the First Continental Congress did not merely instruct consumers to cease purchasing imported goods but also called on colonizers to “encourage Frugality, Economy, and Industry; and promote Agriculture, Arts, and the Manufactures of this Country.” As a shopkeeper who bought and sold homespun cloth, Brown did his part.