What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

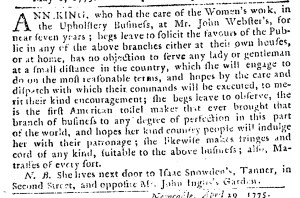

“ANN KING … had the care of the Women’s work, in the Upholstery Business, at Mr. John Webster’s.”

Ann King promoted her experience and expertise when she advertised her services in the May 17, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Journal, following an example set by artisans, male and female, who placed notices in newspapers during the era of the American Revolution. She explained that she “had the care of the Women’s work, in the Upholstery Business, at Mr. John Webster’s, for near seven years.” Although she had worked with Webster for quite some time, he had not acknowledged her contributions to his enterprise in his own advertisements. Artisans only occasionally mentioned their assistants in their newspaper notices, yet King’s advertisement testified to the invisible labor performed by employees (as well as family members) in many workshops. In particular, she reveals that women, whether employees or relative, participated on the production side even though editorials usually depicted them exclusively as consumers.

King took pride in her work. She proclaimed that she “is the first American tostel [tassel] maker that ever brought that branch of business to perfection in this part of the world.” If readers had ever admired the tassels that adorned any of the furniture upholstered in Webster’s workshop, then they should hire King when they were in the market for that item. Even if they were not familiar those tassels, King hoped that her long tenure in a workshop operated by an “Upholsterer from London” who had served “several of the nobility and gentry, both in England and Scotland” would recommend her to prospective clients. She intended for Webster’s reputation to bolster her own. In addition to tassels, King “likewise makes fringes and cord of any kind,” part of the “Women’s work” she had overseen for Webster, and even “Mattrasses of every sort.” She did so with “care and dispatch,” hoping to “merit [the] kind encouragement” of her patrons.

Female shopkeepers and milliners occasionally placed newspaper advertisements, far outnumbering the female artisans who did so. King took to the public prints to advance her business, demonstrating that women did work alongside men in workshops, though their endeavors were sometimes cast as “Women’s work.” Webster upholstered furniture “in the best and newest taste” for many years, depending on King and other women for assistance with the final product. King then leveraged that experience in her effort to earn her livelihood by contracting directly with customers.