What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

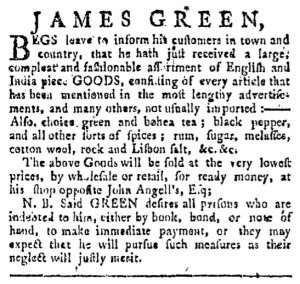

“GOODS, consisting of every article that has been mentioned in the most lengthy advertisements, and many others, not usually imported.”

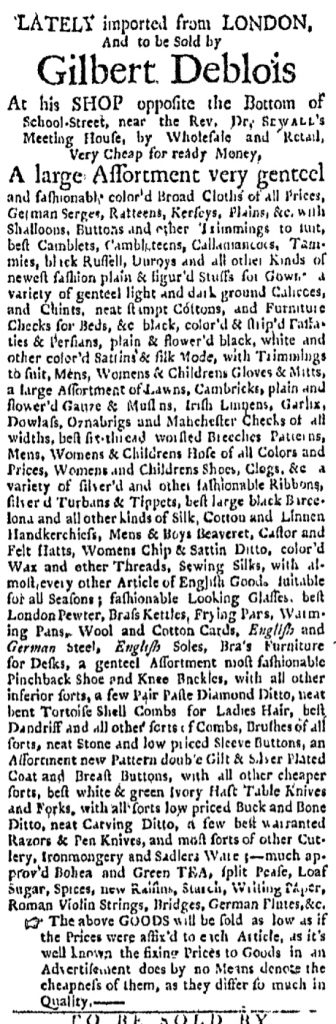

James Green sold a variety of imported goods at his shop in Providence. For several weeks in the late spring and early summer of 1767 he placed a notice that “he hath just received a large, compleat and fashionable assortment of English and India piece GOODS, consisting of every article that has been mentioned in the most lengthy advertisements, and many others, not usually imported.” This claim caught my attention because it so closely replicated an advertisement placed by Gilbert Deblois in the Boston Evening-Post, the Boston Post-Boy, and the Massachusetts Gazette at about the same time. Deblois carried “A complete fashionable Assortment of English & India Piece GOODS, consisting of every Article that has been mentioned in the most lengthy Advertisements, and many others not usually imported.” Green eliminated the italics that consistently appeared in Deblois’s advertisements in all three Boston newspapers, but he otherwise adopted the same language to make a fairly unique appeal.

Many eighteenth-century advertisements included formulaic phrases, such as “compleat and fashionable assortment,” but appropriation of entire sentences that expressed distinctive marketing efforts was not common. Shopkeepers occasionally stated that they carried too much merchandise to list all of it in an advertisement, but rarely did they claim to carry goods “not usually imported.” Green, whose advertisement first appeared in the Providence Gazette on May 23, apparently lifted copy from Deblois’s notice, probably hoping that it would have the same effect of intriguing potential customers and inciting curiosity about what might be on the shelves in his shop. He may have believed that he could get away with treating this marketing strategy as his own if he was the first and only shopkeeper in Providence to adopt it.

Other scholars have demonstrated that news flowed through networks of printers who liberally borrowed news items from other newspapers, reprinting them word for word, sometimes with attribution and other times without. This advertisement suggests that sometimes advertisers engaged in the same practices, keeping their eyes open for innovative marketing appeals formulated by their counterparts in other cities and adopting them as their own.