What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

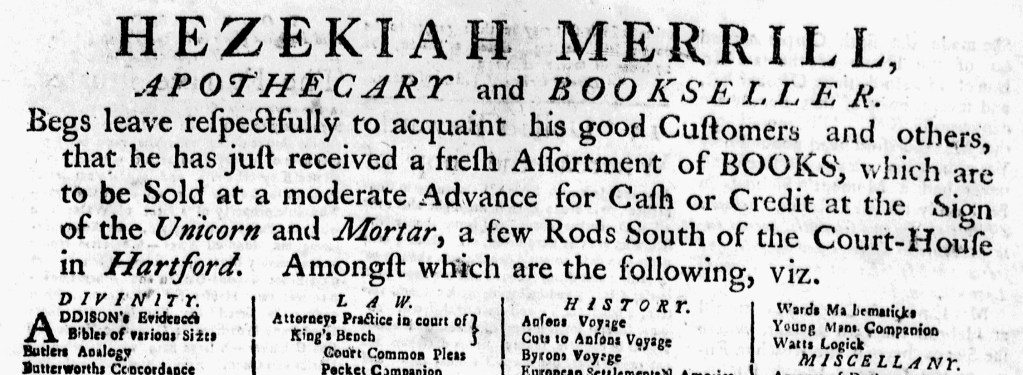

“He has just received a fresh Assortment of BOOKS.”

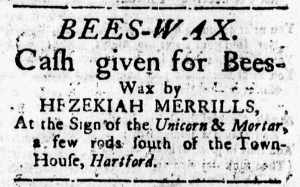

Hezekiah Merrill, “APOTHECARY and BOOKSELLER … at the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar” in Hartford, ran a full-page advertisement in the December 21, 1773, edition of the Connecticut Courant. His name and occupation served as headlines running across the top of the page, followed by an introduction that gave his location and announced that he “just received a fresh Assortment of BOOKS,” which also ran across the entire page. To aid prospective customers in navigating the advertisement, Merrill divided the books by genre with headings that included “DIVINITY,” “LAW,” “PHYSIC & SURGERY,” “HISTORY,” “SCHOOL BOOKS,” and “MISCELLANY.” In smaller type, four columns listed individual titles for sale, compared to three columns for news, editorials, advertising, and other contents on the other three pages of the newspaper. A nota bene in the same size font as the list of titles, ran across the entire page at the bottom. In it, Merrill promoted stationery, writing supplies, and a variety of items often sold by apothecaries. In many ways, Merrill’s advertisement dominated that issue of the Connecticut Courant. It accounted for one-quarter of the total space as well as more space than the other advertisements combined. When readers perused the issue, Merrill’s advertisement became visible to others gathered nearby.

It was not the first time that the bookseller and apothecary published an oversized advertisement in his local newspaper. On May 11, 1773, he ran an advertisement that filled two of the three columns on the second page. He may have made arrangements with Ebenezer Watson, the printer, to produce the advertisement separately as handbills or broadside book catalogs, though no such items have been identified in research libraries, historical societies, or private collections. Compared to newspapers, often preserved by printers or subscribers in complete or nearly complete runs, handbills and broadside book catalogs were much more ephemeral advertising media. Still, in the case of Smith and Coit’s broadside book catalog that also ran as a full-page advertisement in the Connecticut Courant in July 1773, Watson had experience producing advertisements in more than one format for his clients. For Smith and Coit, Watson reset the type, using five columns in the broadside but only four in the newspaper. He could have done the same for Merrill or, even more easily, printed the newspaper advertisement as a separate handbill or broadside book catalog without making any adjustments to type already set. Either way, Merrill, Smith and Coit, other booksellers, and other retailers likely distributed more advertisements in the eighteenth century than happen to survive today.