Who was the subject of an advertisement in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

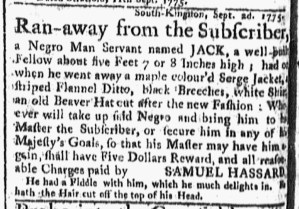

“Ran-away … a Negro Man Servant named JACK.”

Even as it carried essays about the imperial crisis and news about one of the first battles of the Revolutionary War, the October 6, 1775, edition of the Connecticut Gazette also ran advertisements described enslaved men and women who liberated themselves by running away from their enslavers. Each notice encouraged readers to engage in surveillance of Black people they encountered to determine if they matched the description in the newspaper. Each also offered a reward to those who assisted in capturing fugitives from slavery and returning them to their enslavers.

One of those advertisements, for instance, described a “Negro Man Servant named JACK” who fled from Samuel Hassard of South Kingstown, Rhode Island, at the beginning of September. He had managed to elude capture for a month. Hassard described Jack as a “well-built Fellow about five Feet 7 or 8 Inches high,” but did not indicate his approximate age. At the time he departed, he wore a “maple colour’d Serge Jacket, a striped Flannel [Jacket], black Breeches, white Shirt, [and] an old Beaver Hat cut after the new Fashion.” Hassard also mentioned that Jack “had a Fiddle with him, which he much delights in” and that he “Hath the Hair cut off the top of his Head.” Both details made Jack more easily recognizable to readers of the Connecticut Gazette.

In another advertisement, Mortemore Stodder of Groton described a “Negro Girl about 17 or 18 Years old” whose name was once known but did not appear in the notice. Instead, Stodder informed readers that the “thick set” young woman “speaks good English” and “has a Scar across her Nose and another Scar on the top of one Foot occasioned by a burn.” In addition to those distinguishing features, she “[h]ad on a tow Shift, a striped woollen Petticoat, and a brown Gown.” Stodder was so concerned that others might help the young woman remain free that he added a nota bene advising, “All Persons are hereby forbid to harbour, conceal, or carry off the above Servant, on Penalty of the Law.” There would be consequences beyond Stodder’s frustration and displeasure if he learned that anyone aided this young woman in liberating herself.

As the siege of Boston continued, Timothy Green, the printer of the Connecticut Gazette, published the latest entry in “The Crisis,” a series of essays supporting the American cause, new details about the Battle of Bunker Hill, and an address from George Washington, “Commander in Chief of the Army of the United Colonies of North-America,” to the inhabitants of Canada. Even as those pieces each promoted liberty in various ways, Green continued a practice adopted by all newspaper printers. He generated revenue by disseminating advertisements about enslaved people who fled from their enslavers to seize their own freedom.

**********

For all advertisements about enslaved people that ran in American newspapers published 250 years ago today, visit the Slavery Adverts 250 Project‘s daily digest.