What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

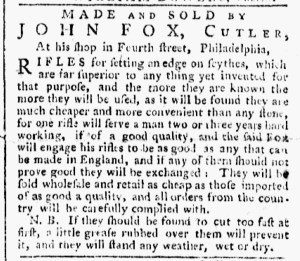

“Fox will engage his rifles to be as good as any that can be made in England.”

John Fox marketed American ingenuity when he advertised scythe rifles, instruments for “setting an edge on scythes,” that he invented. In the May 30, 1774, edition of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, the cutler proclaimed that his rifles “are far superior to any thing yet invented for that purpose.” He was so certain of that assertion that he confidently asserted that “the more [his rifles] are known the more they will be used,” especially since “it will be found they are much cheaper and more convenient than any stone.” Rifles were made of wood, light enough for farmers to carry with them to sharpen the edges of scythes as they worked in the fields; whetstones were much heavier and, in turn, much less convenient for such purposes. Continuing his pitch, Fox claimed that “one rifle will serve a man two or three years hard working, if of a good quality,” and he considered “his rifles to be as good as any that can be made in England.” Furthermore, he pledged to sell his product “wholesale and retail as cheap as those imported of as good a quality.” If any customers were not satisfied once they gave his rifles a try, the cutler offered to exchange any that “should not prove good.”

During the imperial crisis, colonial entrepreneurs promoted “domestic manufactures” or products made in America rather than imported. Such appeals appeared in newspaper advertisements with greater frequency when confrontations with Parliament intensified, especially when colonizers enacted nonimportation agreements in response to the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts. Fox marketed his scythe rifles as relations between the colonies and Parliament once again deteriorated, this time because of duties on tea, the Boston Tea Party, and the Boston Port Act that closed the harbor until residents made restitution. Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet and other newspapers published in Philadelphia carried extensive coverage of the debates and passage of the Boston Port Act and the responses in other cities and towns. Fox’s advertisement appeared immediately below resolutions passed at “a meeting of the inhabitants of the city of Annapolis” on May 25, 1774. They agreed “to put an immediate stop to all exports to Great-Britain” and, upon a date to be determined in coordination with other town in Maryland and “the principal colonies of America,” that “there be no imports from Great-Britain till the said act be repealed.” Perhaps it was coincidence that Fox’s advertisement happened to follow the resolutions from Annapolis. No matter where the two items appeared in relation to each other in the newspaper, the political crisis that inspired the resolutions provided support for Fox’s encouragement to purchase the rifle scythes he “MADE AND SOLD … At his shop in Fourth street, Philadelphia,” as an alternative to imported ones.