What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“THE justly celebrated SPEECHES of the Earl of CHATHAM, and Bishop of St. ASAPH.—Also, A MASTER KEY to POPERY.”

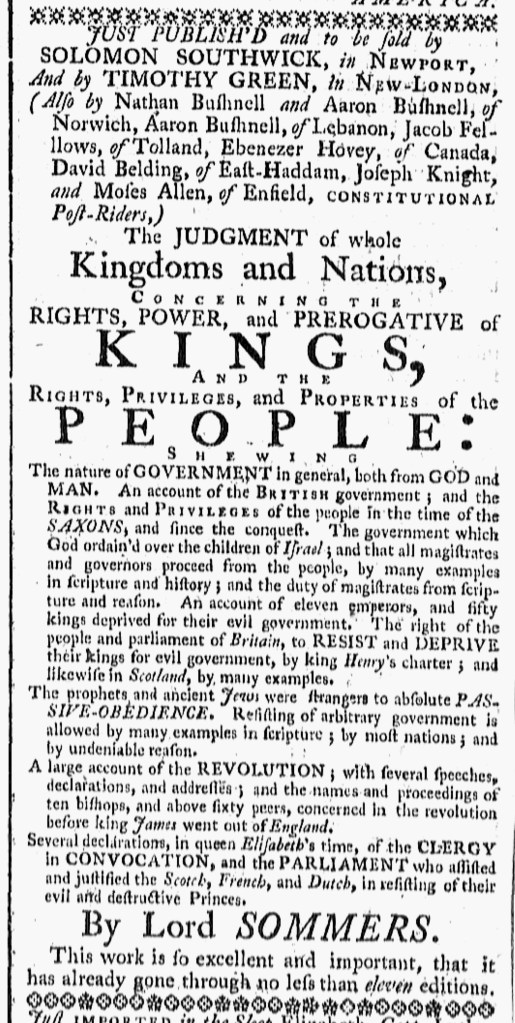

To fill the space at the bottom of the last column on the final page of the September 11, 1775, edition of the Newport Mercury, Solomon Southwick, the printer, inserted a short advertisement that listed several books and pamphlet that he sold at his printing office. Most of them had been featured in longer advertisements, including “the Judgment of whole KINGDOMS and NATIONS, concerning the RIGHTS of Kings, the LIBERTIES of the People, &c.” Southwick’s edition was one of three printed in the colonies in the past two years. The printer also stocked the “justly celebrated SPEECHES of the Earl of CHATHAM, and Bishop of St. ASAPH.” The bishop, a member of Parliament, opposed “altering the Charters of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay,” one of the Coercive Acts enacted by Parliament in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party. When prevented from delivering his speech during deliberations, he instead published it. That earned him significant acclaim in the colonies. William Pitt, the first earl of Chatham, had been “dear to AMERICA” for a decade thanks to his opposition to the Stamp Act. Southwick’s printing office was clearly a place for Patriots to shop for reading material.

The books on offer included “A MASTER KEY to POPERY.” Southwick promoted that volume widely even before taking it to press, disseminating subscription proposals in newspapers throughout New England. They promised an extensive anti-Catholic screed, an exposé of “popery” by a former priest. Southwick either gained enough subscribers to make the project viable or felt strongly enough about the supposed dangers of Catholicism that he printed the book. Once he had copies ready for sale, he linked religion and politics in an advertisement that condemned “the infernal machinations of the British ministry, and their vast host of tools, emissaries, &c. &c. sent hither to propagate the principles of popery and slavery, which go hand in hand, as inseparable companions.” Such prejudices resonated as colonizers expressed dismay over the Quebec Act, yet another of their grievances against Parliament. That legislation gave several benefits to Catholic settlers in territory gained from the French during the Seven Years War, an insult to Protestants in New England who had sacrificed so much in fighting the British Empire’s Catholic enemies. For Southwick and many of the readers of the Newport Mercury, support for the American cause and anti-Catholicism went hand in hand during the imperial crisis and the beginning of the Revolutionary War.