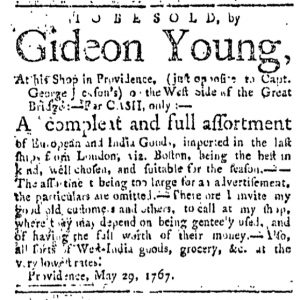

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The assortment being too large for an advertisement, the particulars are omitted.”

Shopkeepers, including Gideon Young of Providence, frequently promoted the “compleat and full assortment of European and India Goods” they imported, stocked, and sold to colonial consumers. Most emphasized consumer choice, enticing potential customers with visions of selecting textiles and housewares that appealed to their own tastes and fit their budgets. A “compleat and full assortment” of merchandise meant that customers experienced significant independence when they went shopping, rather than being expected to accept whatever happened to be on the shelves. Such freedom empowered colonial consumers; advertisers hoped this would encourage them to make more purchases as they explored and considered all the possibilities before determining which goods to buy.

Many advertisers set that process in motion by inserting lengthy lists of their inventory in their commercial notices, prompting potential customers to imagine possessing their merchandise – wearing particular fabrics and adornments or using and displaying specific housewares – even if they had not yet considered visiting any shops. Advertisers sought to stimulate demand by introducing readers to items that they might not have previously even realized that they desired. Eighteenth-century shopkeepers considered enumerating dozens or even hundreds of items in a list-style advertisement one effective way of achieving that goal.

Gideon Young, however, took a different approach as he encouraged potential customers to think about his “compleat and full assortment of European and India Goods.” He did not list any specific items, but instead stated, “The assortment being too large for an advertisement, the particulars are omitted.—Therefore I invite my good old customers and others, to call at my shop.” Such an invitation may have been just as powerful as a list of specific goods. It created a sense of mystery and anticipation by prompting readers to imagine the size of Young’s inventory and the variety of his goods that prevented him from offering a preview in the newspaper. It evoked curiosity and encouraged window shopping that might lead to actual purchases when readers came to investigate the “complete and full assortment” of merchandise on their own.

Young may have been making a virtue of a necessity when he adopted this sort of appeal. While this marketing strategy occupied less space on the page and presumably incurred lower costs, this did not necessarily make it less effective than posting a list-style advertisement. Instead, Young’s description of his merchandise – “the best of its kind, well chosen, and suitable for the season” – was designed to convince potential customers to visit his examine his wares rather than visit shops where the proprietors had not exercised so much care in selecting which goods to stock.