What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Romans’s map of the seat of war near Boston.”

At the end of July 1775, Nicholas Brooks began running a new advertisement in the Pennsylvania Ledger. It first appeared on July 29 and then again in the next two issues. In it, Brooks hawked a “curious collection of GOODS” that he sold at his shop on Second Street in Philadelphia. He listed everything from sword belts and “beautiful guns for gentlemen officers” and “gilt and stone buckles for ladies” to “razors in new fashion cases, very convenient for traveling” and “cork screws of the best quality” to “a very elegant assortment of ladies and gentlemans pocket books in Morocco velvet, worked with gold and silver” and “a variety of music of the most approved tunes.” He also stocked “a very elegant assortment of pictures and maps in books or single.” Brooks had already established “PRINTS and PICTURES” as a specialty.

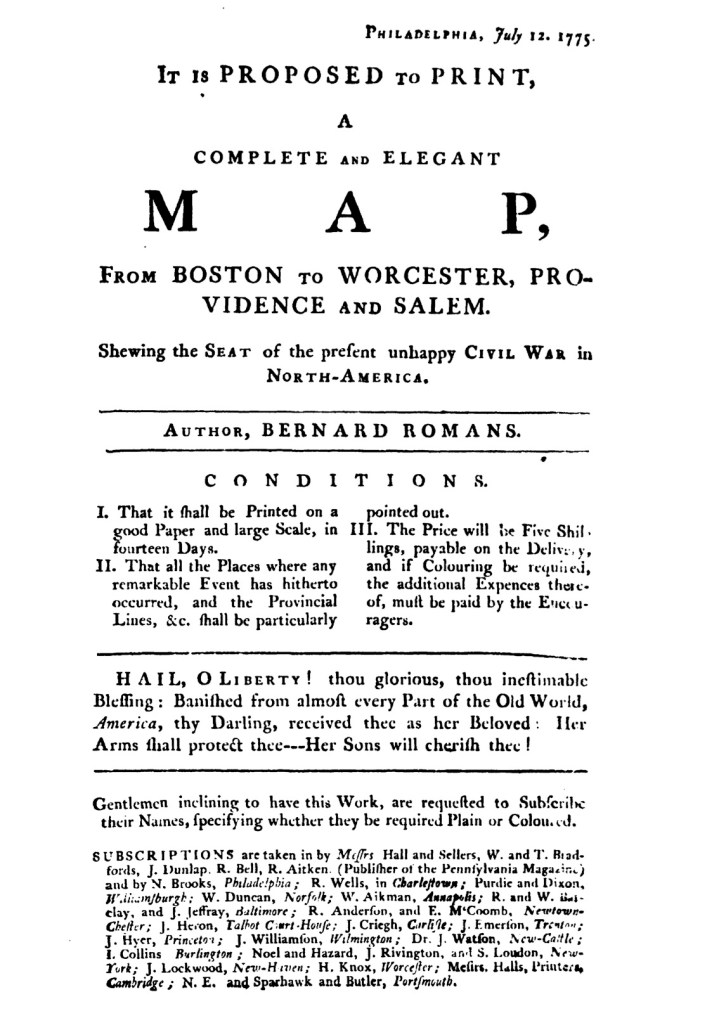

He concluded this advertisement with a nota bene that indicated he sold “Romans’s map of the seat of war near Boston,” but he did not say anything more about that item. In addition, neither Brooks nor Bernard Romans, the cartographer and “AUTHOR” of the map, previously advertised the project in the Pennsylvania Ledger or any of the other newspapers printed in Philadelphia at the time. Perhaps Brooks expected that readers were familiar with a broadside subscription proposal, dated July 12, that had been circulating or posted around town and beyond. The subscription proposal featured the same copy as the advertisement for the map that ran in the August 3 edition of Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, though the newspaper notice listed only local agents while the broadside gave a much more extensive list of printers, booksellers, and others who collected subscriptions in towns from New England to South Carolina. James Rivington apparently adapted the broadside rather than composing copy for the advertisement when he inserted it in his newspaper. That broadside documented a sophisticated network for inciting demand for the map and distributing it to subscribers. In addition to the five printers and booksellers who collected subscriptions in Philadelphia, twenty-two local agents in eighteen towns in ten colonies collaborated with Brooks and Romans. That list represented an “imagined community,” a concept developed by Benedict Anderson, of readers and consumers near and far who simultaneously examined the same map “Shewing the SEAT of the present unhappy CIVIL WAR in NORTH-AMERICA.”

Brooks did not limit his marketing of the map to the broadside subscription proposal and the nota bene at the end of an advertisement that cataloged dozens of items available at his shop. He eventually ran newspaper advertisements devoted exclusively to the map, seeking to generate more interest and demand for such a timely and important work.

**********

The Massachusetts Historical Society has digitized Romans’s map, accompanied by a brief overview of its significance and a short essay about Romans and other cartographers active during the era of the American Revolution.