What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The WITS of WESTMINSTER.”

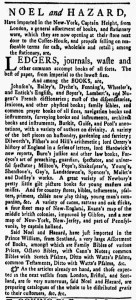

The headline alone likely the attention of many readers of the July 5, 1773, edition of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury. It invited them to learn more about a book that Hodge and Shober, printers, and Noel and Hazard, booksellers, offered for sale at their shops, likely an American edition of a book published in London in 1772. In the advertisement immediately above, Samuel Dellap announced that he stocked copies of The Wits of Westminster “just published.” Dellap had recently published and advertised an American edition of George Alexander Stevens’s popular Lecture on Heads. In the second advertisement, the main title of the book served as the headline, while, in both advertisements, the extended secondary title doubled as copy. When the advertisers described the contents as “A New select Collection of Jests, Bon Mots, humorous Tales, brilliant Repartees, Epigrams, and other Sallies of Wit and Humour, chiefly new and original, being and agreeable and lively Companion for the Parlour, or wherever such a Companion is most necessary and pleasing” they merely copied what appeared on the title page, as many printers, publishers, and booksellers did during the period.

The lengthy secondary title provided additional advertising copy, declaring that The Wits of Westminster contained “more Novelty, than has appeared since the Time of Joe Miller’s Publication.” According to the British Museum, Joe Miller (1634-1738) was a comic actor whose “reputation as a comedian off-stage was enhanced by the posthumous publication of ‘Joe Miller’s Jests’ in 1739.” That first edition included 247 numbered jokes. Subsequent editions included even more. Miller and, especially, the witticisms collected in the books that bore his name gained so much notoriety that often-repeated jokes became known as “Millerisms.” A little more than a century after Miller’s death and the publication of Jests, Charles Dickens made reference to the comedian in A Christmas Carol (1843). Framing The Wits of Westminster as the most entertaining collection of jokes since Jests, published more than thirty years earlier, likely resonated with prospective buyers who would have understood the cultural reference.

In case that was not enough to incite interest, Hodge and Sober and Noel and Hazard added a short poem, a meditation on humor, that distinguished their advertisement from others. “Haste thee, Nymph, and bring with thee, / Jest and youthful Jollity; / Sport that wrinkled Care derides. / And Laughter, holding both his Sides. / True Wit is like the brilliant Stone, / Dug from the Indian Mine; / Which boasts two various Powers in one, / To cut as well as shine.” Humor, the poem observed, had the potential both to amuse and to wound, depending on how deployed. Many of the “Bon Mots,” “brilliant Repartees,” and “Sallies of Wit” in The Wits of Westminster likely did both at once, the humor sometimes depending on belittling the subject of the jest. While intended primarily for amusement, the book, like the poem in the advertisement, required readers to think about what made something funny. Even frivolity required contemplation, the advertisers asserted in their efforts to convince prospective buyers to indulge themselves by purchasing The Wits of Westminster.