What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Mr. STRATON will begin a Course of LECTURES.”

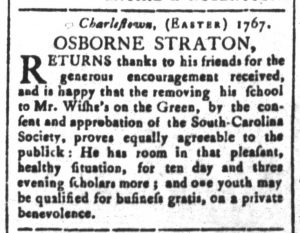

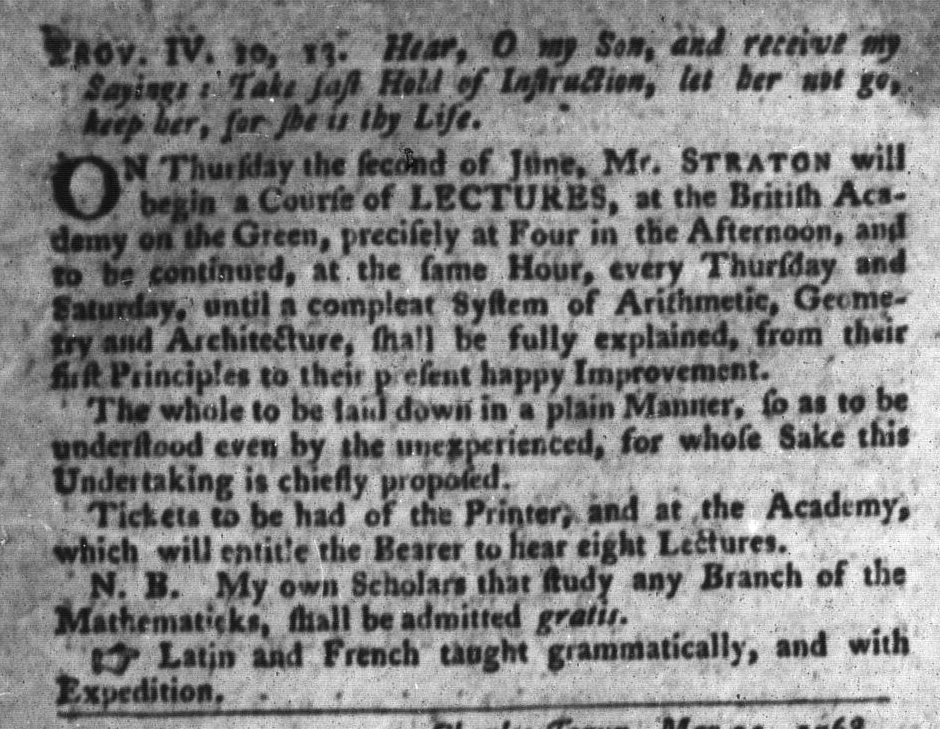

Schoolmaster Osborne Straton frequently advertised his “British Academy on the Green” in the newspapers published in Charleston in the late 1760s. Although he usually sought students who would enroll in his academy, on occasion he offered other opportunities for instruction to the residents of the city. For instance, during the summer of 1768 he delivered “a Course of LECTURES” that took place on Thursday and Saturday afternoons. Straton established a theme for his lecture series, proposing to explicate “a compleat System of Arithmetic, Geometry and Architecture” and promising that each “shall be fully explained, from their first Principles to their Present happy Improvement.”

Compared to the many other schoolmasters and –mistresses that advertised in the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal and other newspapers, Straton positioned his British Academy as one of the most elite options available to prospective pupils in the colony. He even concluded his advertisement for the lecture series by noting that he taught Latin and French, reminding regular readers of the extensive curriculum they had encountered in his previous advertisements. For this particular “Course of LECTURES,” however, Straton underscored that he intended to engage general audiences: “The whole to be laid down in a plain Manner so as to be understood even by the unexperienced, for whose Sake this Undertaking is chiefly proposed.” Whether they sought entertainment or elucidation or a combination of the two, Straton invited members of the general public who might not otherwise enroll in his school to benefit from a series of lessons pitched specifically to their level of prior knowledge and experience with the subjects he covered.

Yet he did not throw wide the doors to the British Academy. He expected those who attended the lectures to pay for the experience. He carefully regulated who entered via a system of tickets, sold both by Charles Crouch at the printing office and Straton at the academy. Each ticket “entitle[d] the Bearer to hear eight Lectures.” Straton’s current students who “study any Branch of the Mathematicks” gained free admission, a perquisite of enrolling in his more extensive courses.

The schoolmaster’s verbose advertisements gave readers a sense of the curriculum and teaching style adopted at “the British Academy on the Green.” Even though he oversaw an elite academy, Straton also advertised scholarship opportunities for students who otherwise would not have had the means to enroll in his classes. This lecture series, designed for the benefit of “the unexperienced,” served as another form of outreach to audiences beyond the local gentry. Despite the stuffy persona he frequently cultivated in his advertisements, Starton also managed to communicate an interest in providing educational opportunities for the general public and not just the scions of the elite who could afford to enroll in his academy.