What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

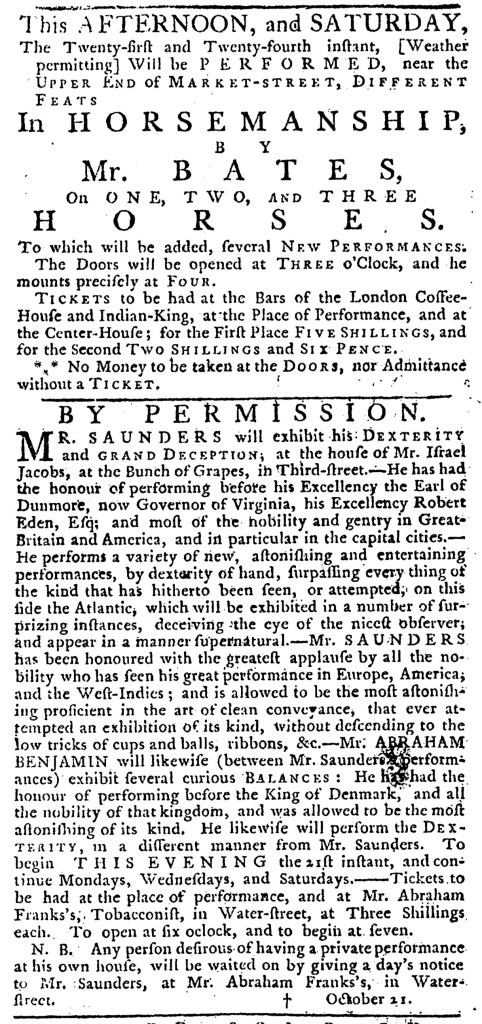

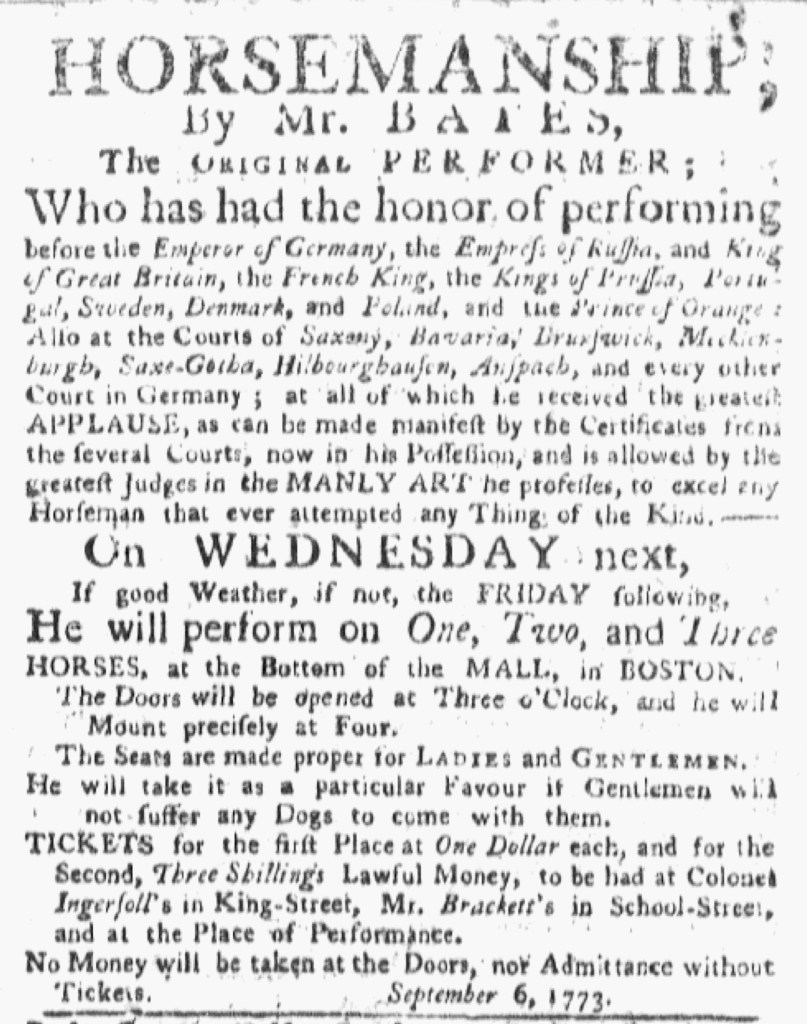

“HORSEMANSHIP, By Mr. BATES.”

Not long after Mr. Bates concluded his performances in New York, he arrived in Boston and began advertising exhibitions of his feats of horsemanship in the newspapers there. He commenced with notices in the Boston Evening-Post and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy on Monday, September 6, 1773, informing ladies and gentlemen of the city about his performance on Wednesday or, if the weather did not permit, on Friday.

As he had done in his advertisements in New York, he deployed “HORSEMANSHIP” as a headline for his notice and then introduced himself as “The ORIGINAL PERFORMER; Who has had the honor or performing” for a longlist of royalty in Europe. He declared that he earned “the greatest APPLAUSE” from those regal audiences, but did not expect colonizers in New York to take his word for it. Instead, he had “Certificates from the several Courts” that they could examine. In addition, he asserted that the “greatest Judges in the MANLY ART” of horsemanship considered his skills “to excel any Horseman that ever attempted any Thing of the Kind.” Bates hoped that the promises of such a spectacle would entice audiences in Boston to attend his show.

He had reason to feel confident in the effectiveness of this marketing strategy. After all, he gave the same pitch in New York. He may have delivered newspapers, clippings, or perhaps even handbills from that city to the printing offices in Boston or he may have copied out the advertisement from one of those sources. Whatever method he deployed, he remained consistent in how he introduced himself and described his skills to prospective audiences, likely sticking with what worked. He also repeated another technique that he used in New York, encouraging anyone interested in the performance to acquire tickets quickly because “No Money will be taken at the Doors, nor Admittance without Tickets.” Rather than wait until the time and day of the show, Bates aimed to generate ticket sales in advance. Through experience, he devised a system that he believed worked best for inciting interest and securing his livelihood.